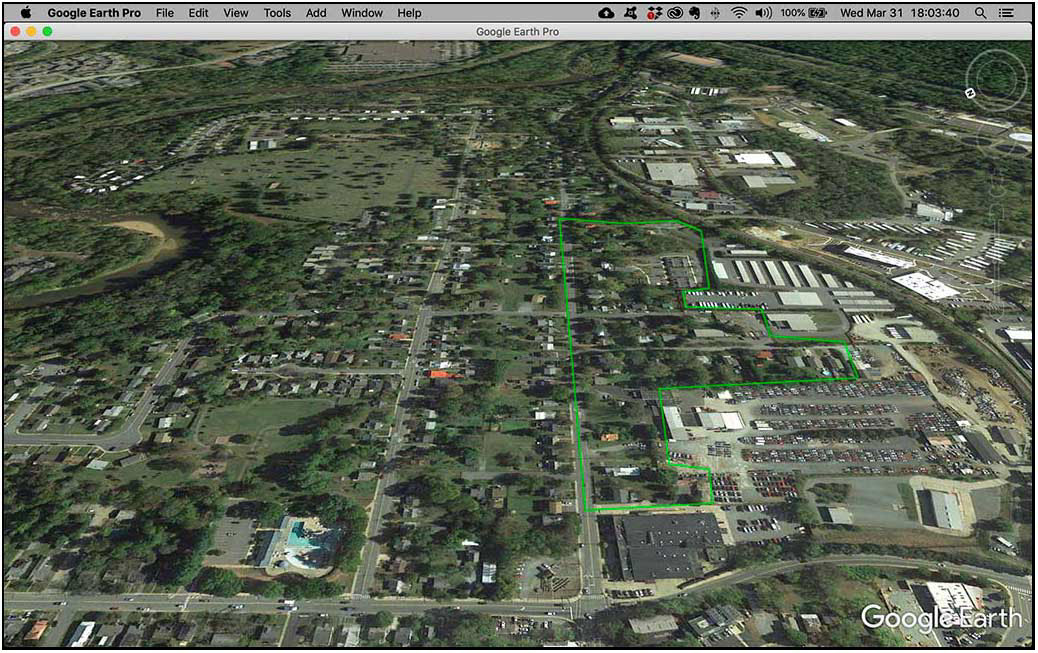

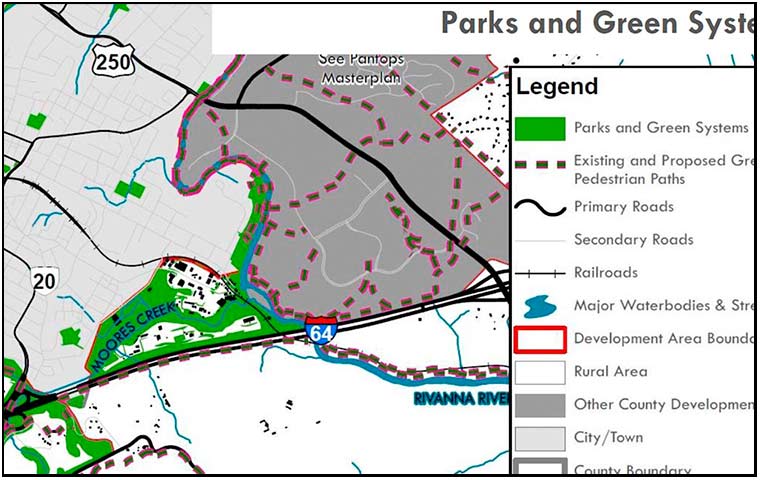

People in the City are nervous about the planning currently going on. What will the plan do to the City? How does the land use map work with zoning? What will it mean? The photo above is Franklin Hill, a forested hillside northwest of Monticello. Once upon a time the site of the Woolen Mills Park. The county land use map addresses this area, no worries! It is shown on the map. Parks and Green systems.

Nothing to worry about.

Author Archives: WmX

Urban Renewal 2.0

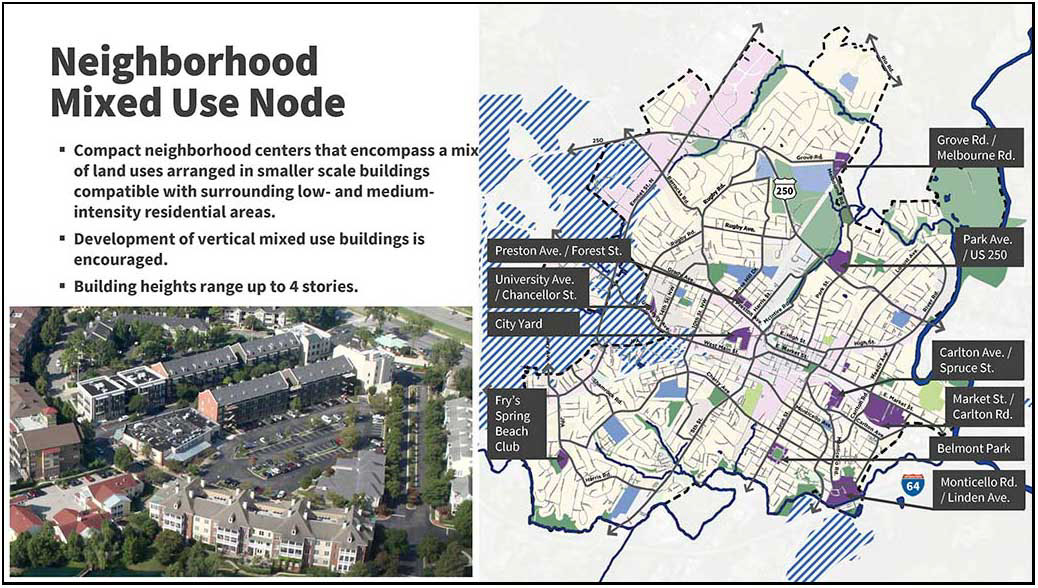

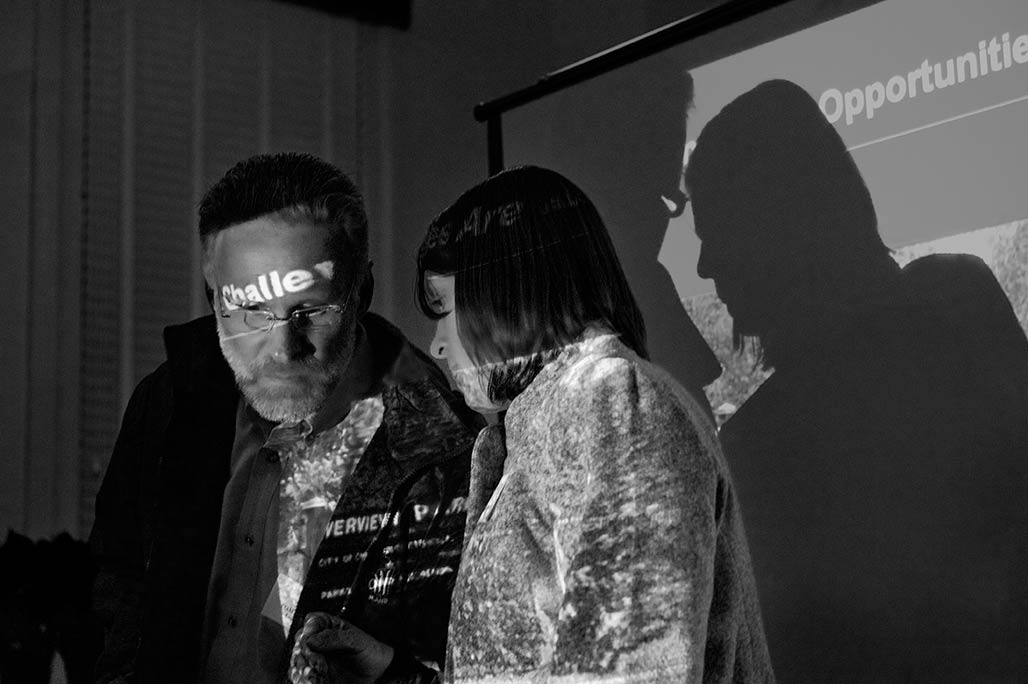

page 17 of a slideshow shown at the 3/30/2021 Planning Commission work session. https://boxcast.tv/channel/iweiogrihxlnnvn2sxqx

From the fog of COVID, a draft land use map has emerged. The planning document looks to be a blue print for urban renewal and the starting gun for the teardown of affordable housing in the Woolen Mills Neighborhood.

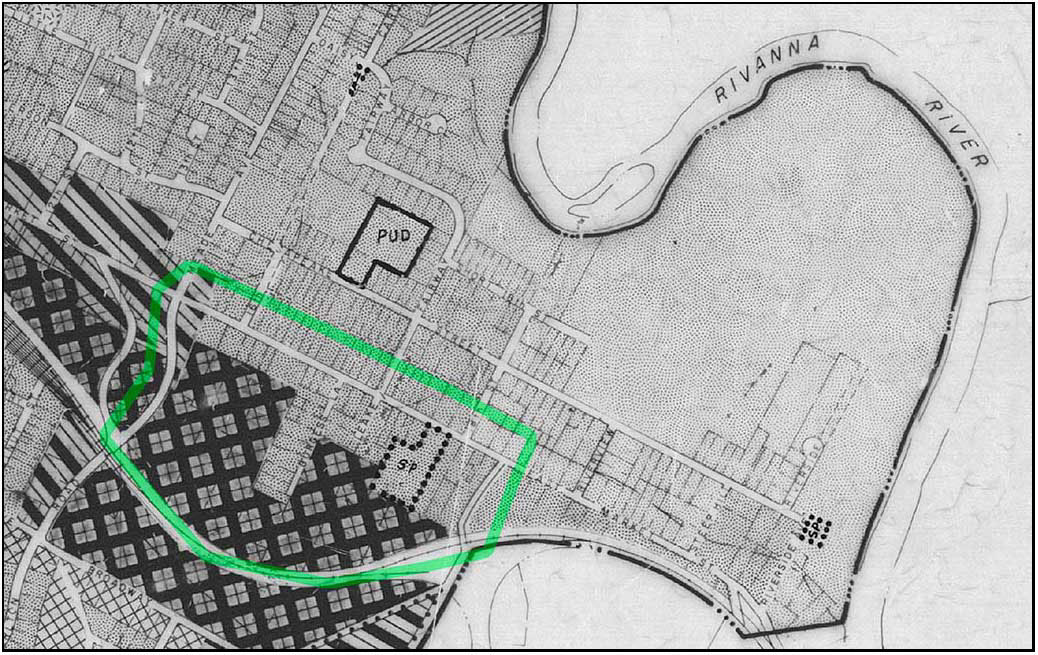

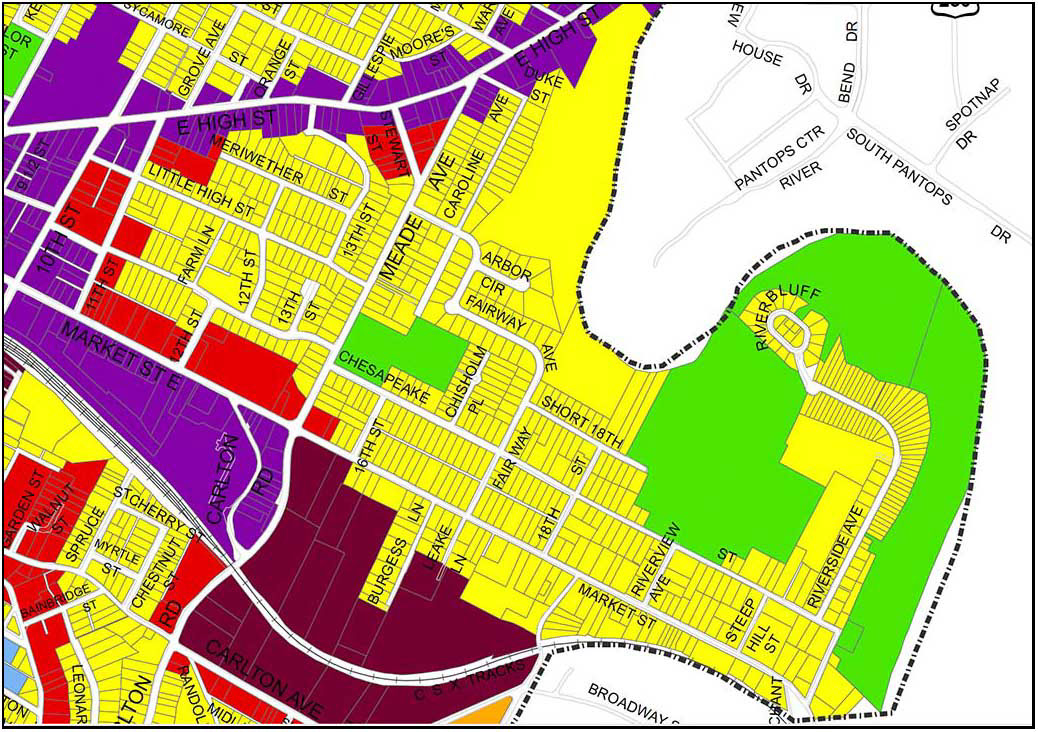

The above map is a detail from the draft Land Use Map which was discussed at the Charlottesville Planning Commission’s 3/30/2021 work session. Of particular interest, the purple “Neighborhood Mixed use node” placed on the Woolen Mills neighborhood. At 40 acres, this is the largest such node proposed in the City.

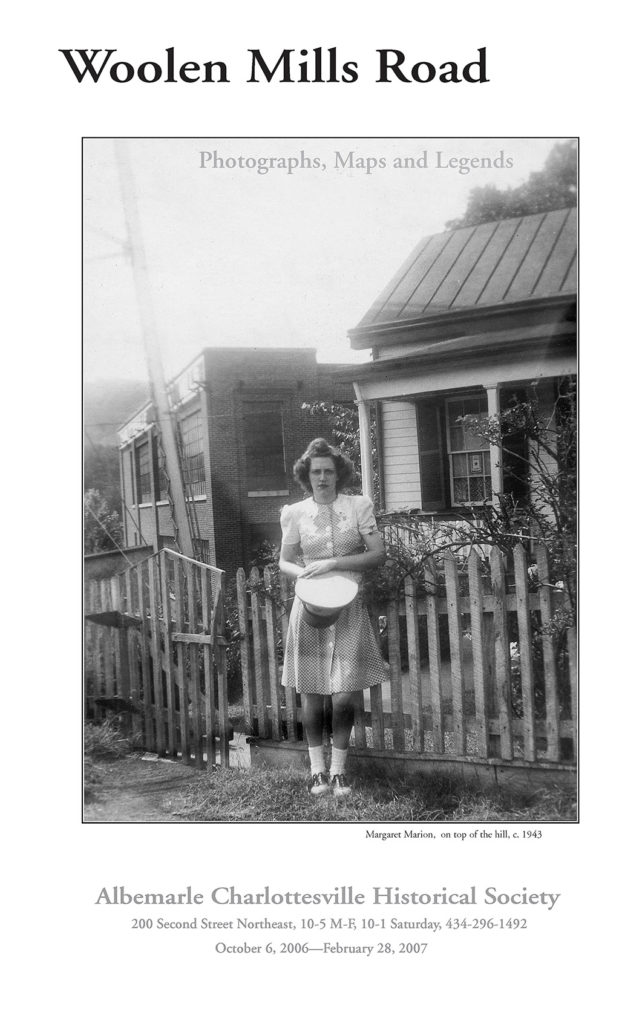

People have lived in houses lining the south edge of Market Street between Meade Avenue and Franklin Street for 135 years. You do not know their names. They are not rich or famous. They call this area their home.

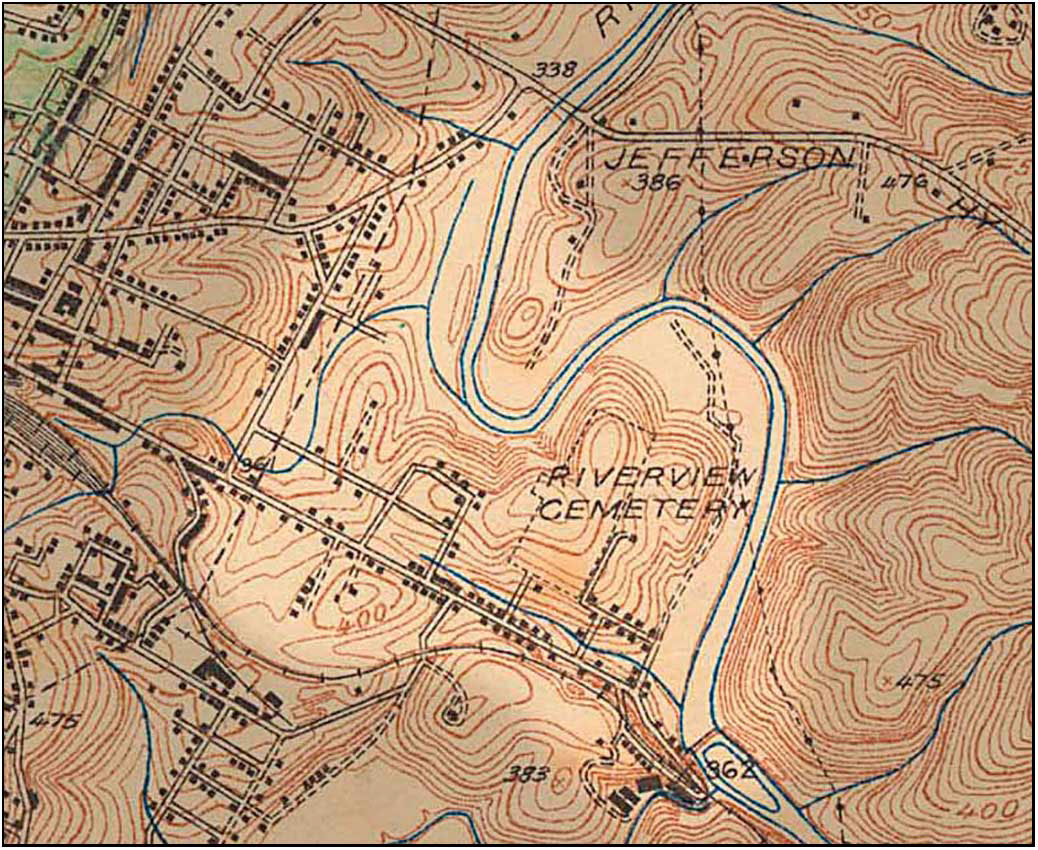

detail from 1935 topo map. In 1935, 19 houses lined the southern edge of Market Street between Meade and Franklin

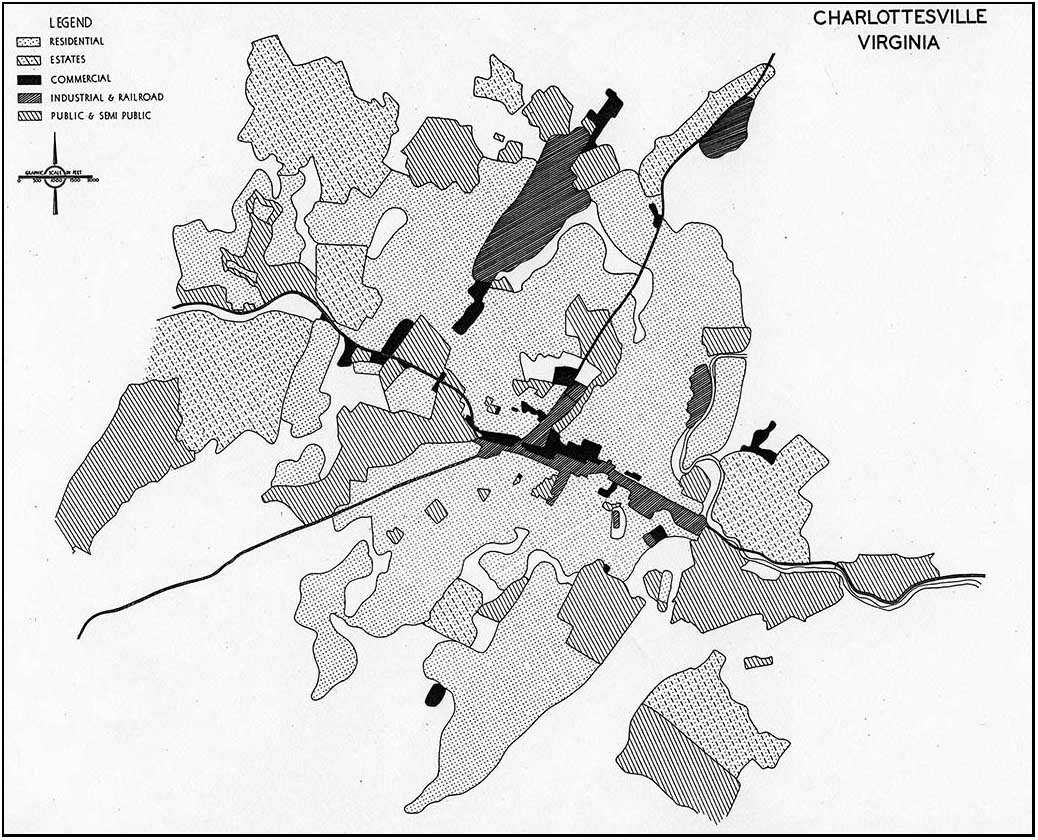

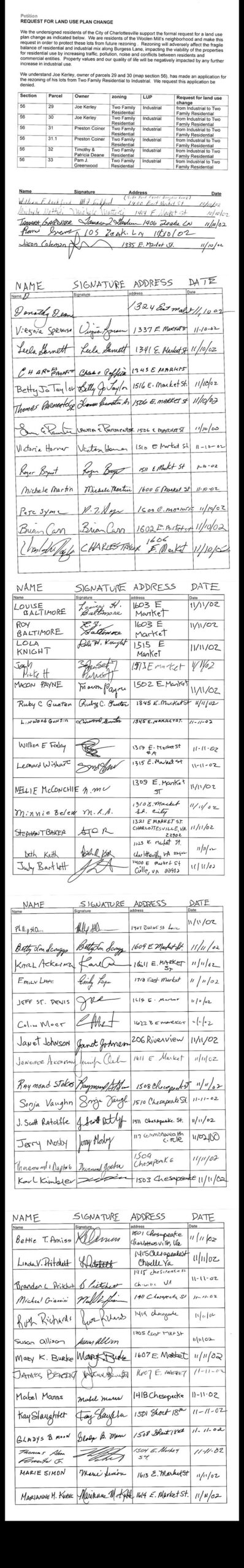

Since its first comprehensive Plan in 1958 the City has represented the bifurcated planning laid across the backyards of these Market Street residential properties in a series of zoning and land use maps.

For 60 years these maps have recognized two elements. The maps show proposed manufacturing, industry, and business in the southern 70% of the land and residential uses bordering Market Street and Franklin.

This bifurcated zoning/land use was placed in the backyards of houses and residential properties fronting on the southern edge of Market Street. This allows manufacturing-industrial-business adjacency to residential use, cheek to jowl.

The Woolen Mills Neighborhood has appealed for thoughtful, community-based study and correction of this poorly thought out land use/zoning layout for decades. The Woolen Mills first formal request for a small area plan was made of the City Council at their August 1, 1988 meeting.

In 2013 the Woolen Mills Small Area Plan request had risen to the top of the SAP list, but was bypassed for more exigent planning challenges (Route 29 North, Starr Hill and Cherry Avenue).

The “new” draft Land Use Map mimics the “Future Diagrammatic Land Use Map” produced by Harland Bartholomew and Associates for the City of Charlottesville in October 1956 in regards to its blanket treatment of the residential community south of Market between Meade Avenue and Franklin Street.

(HBA were the primary architects of “urban removal” in the United States back when neighborhoods were torn down with bulldozers.)

Hoping against hope that the powers that be will rethink the proposed upzoning and destruction of the residential neighborhood fronting on the southern edge of Market Street.

We live here. Please…

City Planning Commission member Sue Lewis advised residents from the Woolen Mills neighborhood that “you should have mobilized sooner. When you are living in the middle of a potentially unwanted development, you should act before something happens.”—7/14/1988 Planners approve warehouses in Woolen Mills district by Kay Peaslee Observer staff writer

I think this issue about, you probably can go all throughout the City and find properties that are, inconsistencies between the land use and comprehensive plan and I think it behooves citizens to be

alert to every single one of those fragments that are left in the City. And I think we are working overtime to try and identify them all and I think it is grossly unfair that everyone should anticipate these areas that are caught in between.I believe though that the Woolen Mills Neighborhood has not had the benefit of a real plan for how these acres and acres of M1 and B3 uses are going to be developed over ten or twenty years and other neighborhoods have had the benefit of that and it’s made a significant difference in how land will develop.

I know Ridge Street neighborhood had a neighborhood plan done for it, for properties that were zoned what we thought was inappropriate for the neighborhood. That project looked at it through another lens, it recommended down-zoning, it recommended a different kind of housing, and seven years later, the kind of housing that the City had anticipated was done because we dared imagine what a different and better use would be for those properties.

I think it is long overdue for the Woolen Mills that they have a clear signal of where their neighbor-hood is going, and not be done in this piecemeal fashion.

So I guess my hope would be that out of this process, given the talent that they have in their neigh-borhood, that they get together and decide that proactively we are going to tell you what the future of our neighborhood is going to be, and it is not going to continue to be an erosion of the things that they have come to feel anchor their neighborhood, that’s the residential use and some of the mixed use strategies that they have.

So that is one thing I would hope would come out of this process, and I guess you’ll have to wait to hear the outcome, for another two weeks.— Maurice Cox, April 7, 2003

View from the right bank of Moores Creek

Flu Time—Memories of a child.

Bettie Frances (Baltimore) Harlow stands with nephew Roy. Bettie was a weaver at the mill, paid by out-put, seven cents per yard of cloth produced. Her husband, Marcellus Carter Harlow, worked in the millʼs wet-finishing department. The Harlows were Aunt Bettie and Uncle Cel to young Roy.

I had a little bird,

Its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.

In October of 1918 200,000 people died in the United States

from the Spanish Flu. Thirty-seven year old David Baltimore,

a son of the Woolen Mills village died October 25, 1918.

How to tell a story of a neighborhood? Through maps

and legends, the reading of tea leaves, received mythology.

Imperfectly. Through the memories of a child.

Roy Baltimore and his parents moved in with Cel and Bettie Harlow in the west end of Woolen Mills village (1606 WMRd) shortly before his fatherʼs death…

I had the flu as I was coming here, and when I got here I had it. And I remember as clear as a bell what the treatment for flu was by this particular Doctor, it was a dose of castor oil, every morning, I used to dread it, that went on for several days, I donʼt know for how long.

I was born in Richmond. My father was a conductor on the railroad, a yard conductor, in Richmond. I would think that the date would have been around 1916 when he developed an illness, I was born in 1914. He developed an illness, had a leaking valve in his heart and it killed him. He died when I was four and I came to live with my Uncle Cel in that brick house across the street here (1606 Woolen Mills Road).

See my father was brought here, from Richmond before he died. I think he lived here maybe eight to nine months, I donʼt know how exactly how long, before he died.

I vaguely remember him because I was just a little over four years old when he died. But I remember once he was sitting on the porch, I have a picture of him sitting on that porch over there, and there was a snake in the yard, and I was getting close to the snake and he cautioned me about it.

I can remember that.

Itʼs a strange thing how your memory can go back and pick up little isolated items, because prior to moving here from Richmond, I can remember well the layout of the apartment we had over on Church Hill. The kitchen was back here, there was a combination dining room bedroom ahead of that and another small room ahead of that. And I can remember my mother telling me “Get your toys up because your daddy is going to be here pretty soon.” Words to that effect, and I couldnʼt have been more than four years old at that time. Thatʼs remarkable that memory is in your mind.–RB

Renewal

new life

County and City cooperate!

Michele Simpson, RWSA senior civil engineer, touring folk around the new Rivanna Pump Station following the ribbon cutting, October 5, 2017..

It was a seven year process from the old pump station to the new station. This is the circular stairway to the old RPS (Rivanna Pumping Station). A smelly hell-hole, next to a park in a residential neighborhood.

December 8, 2010. Tom Frederick of the RWSA and Janice Carroll of Hazen Sawyer confer during slide presentation to the Woolen Mills neighborhood regarding RWSA’s Rivanna Interceptor Sanitary Sewer Pumping Capacity Improvements. The meetings continued for almost two years.

At the ribbon cutting for the new Rivanna Pump Station October 5, 2017 Charlottesville City Councilor Kathy Galvin spoke about the process.

“It is through that long series of meetings, those many many chats over coffee, walking the site, getting everybody to understand the significance of this, both at the very local level, which is the neighborhood, and then at the City level, then at the County level, then at the regional watershed level, it was a major learning experience… It was a big issue then. So I want to say thank you to the community for being good stewards of your home and of your neighborhood and of your city and of your region.”

listen here

Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna (05)

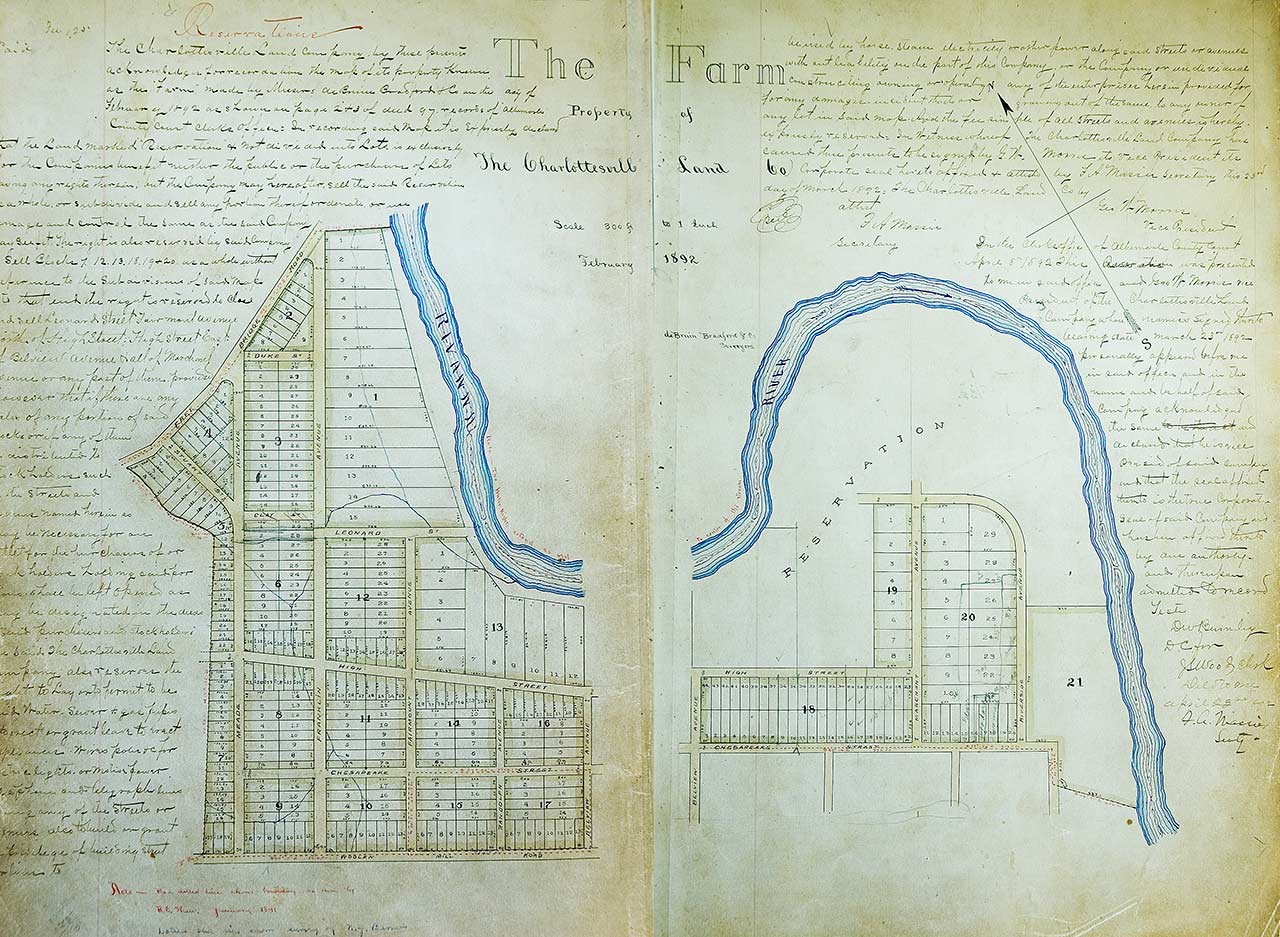

The timing of The Farm development did not bode well for its immediate success in 1892, the United States slid into one of its worst economic depressions in history. In November 1892, George W. Morris, President of the Charlottesville Land Company, reported to the company’s stockholders, “Booms have collapsed all over the State, and much money has been lost. A period of reaction has set in. It is not the intention of this report to hold out to any stockholder the hope of large and sudden profits from his stock. It will take time to realize on our assets…. But our properties practically belt the City of Charlottesville, and Charlottesville has never been so prosperous as she is today, nor has she ever grown so fast as she has done during the past twelve months. Our properties must become more and more valuable, and must eventually, even the most remote pieces, be in demand.” Despite these encouraging words, the Charlottesville Land Company sold very few individual lots at The Farm to suburban homebuilders; instead, over the next few years, the company sold off entire blocks of its development-many of them to Henry Clay Marchant, the wealthy proprietor of the Charlottesville Woolen Mills which operated on adjacent property along the Rivanna. Marchant maintained his large tract of The Farm in its historical agricultural use, as sod pastureland. The Charlottesville Land Company’s earlier plans–for riverside villas and a substantial suburban neighborhood–fell victim to the vagaries of the national economic cycle.

As the Charlottesville Land Company sold off The Farm in large blocks, one local developer purchased a nearly 28-acre tract of The Farm, envisioning a more depression-proof market for lots. This tract included a large portion of the “reservation” contained in 1892 plat of The Farm. Here in 1893, J.W Marshall and his business partners established the Riverview Cemetery, where lots would accommodate the dead rather than the living. The landscaped cemetery occupied the hilltop overlooking the Rivanna with a fairly regular pattern of blocks and lots. The cemetery tract also included land in the floodplain, which was laid out with a meandering walk where visitors could move down the hill from the graves to the banks of the river. As in the case of the Charlottesville Land Company plat for The Farm, the Riverview Cemetery plan clearly acknowledged the beauty and aesthetic character of the Rivanna. Both envisioned taking land that had been in agricultural production for over a century and a half and devoting it to new uses, ones that would cultivate, not crops, but the aesthetic sensibilities Charlottesville residents and visitors for area’s natural landscape.

Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna: The Unexecuted Plans For a River City is by Daniel Bluestone and Steven G. Meeks. This article was published in Volume 70 2012 of the Magazine of Albemarle County History by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. Copies of the Magazine are available at www.albemarlehistory.org

Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna (04)

In his first lease of The Farm in 1866, Farish made restrictions that suggest he viewed the Rivanna as more than a property boundary, source of waterpower, commercial navigation artery, or ecological system. In addition to these, he viewed the river in scenic and aesthetic terms. In leasing The Farm to James E. Cooke, Farish designated areas where Cooke could gather fallen timber, but declared that Cooke, “binds himself not to injure, deface, cut down or destroy any trees whether they be for use or ornament growing upon the …leased land and more especially the prime Forest situated near the River, nor to plow up or otherwise break the sod on the steep hillside next to the River and west of the prime Forest but to continue the same in grass as it now is and keep it cleared of bushes and other filth that may grow upon it to the injury of the Grass.” This attention given to the forest, grass, and hillside suggests an aesthetic calculus concerning the river and its banks that went beyond the usual economic terms of the relationship between local residents and the Rivanna. This aesthetic vision proved central to Paul Goodloe McIntire as he shaped his own plans for the river.

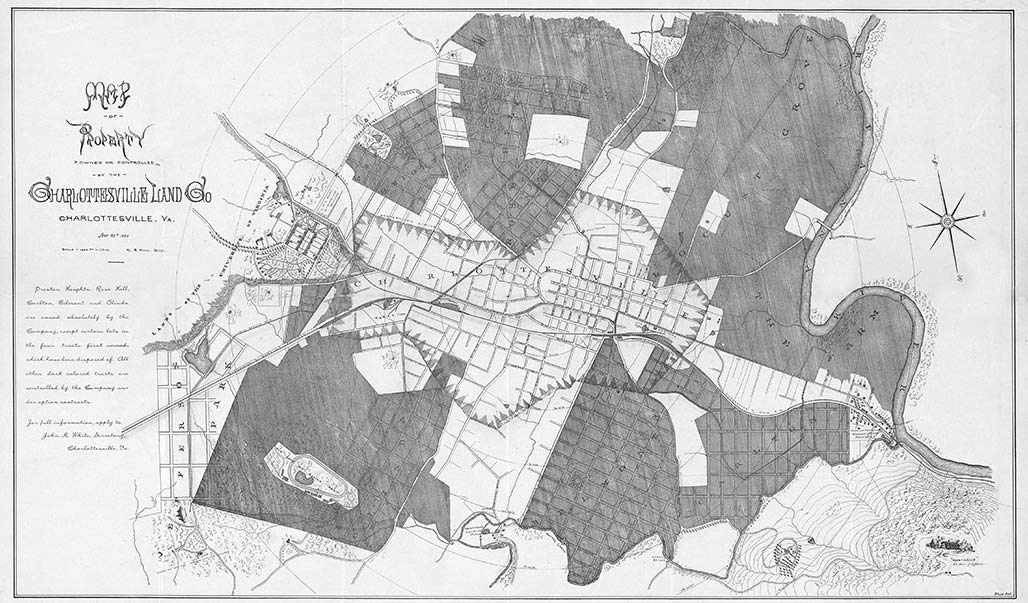

In 1891, Thomas Parish’s heirs sold the “prime Forest,” the steep-hillside with its grass sod, and nearly 200 acres of The Farm’s riverside land to the Charlottesville Land Company. The Charlottesville Land Company was the leading developer of residential subdivisions and had converted farmland on all sides of the downtown into modern suburban neighborhoods to accommodate Charlottesville’s expanding population. The Company filed the plat for its subdivision in February 1892; it appropriated the familiar historical name, calling the development The Farm. The plat established block, street, and lot lines, making the streets generally 50 feet wide and giving the typical residential lots 50 feet of street frontage and between 175 feet and 200 feet of depth. The residential lots closest to the Rivanna had a different form. These lots were twice as wide, with generally 100 feet of street frontage, and much deeper, ranging from 250 feet to 700 feet deep. Thus, the subdivision layout reflected the continuing value of the Rivanna in the region; it also clearly assumed that the riverside lots would be more valuable because of the scenic and aesthetic character of the River. The depth of some of the lots might also have reflected the continuing expectation that the river would flood and submerge the back yards of the most substantial residences in the new neighborhood. Moreover, the Charlottesville Land Company initially left the area of the “prime Forest,” the steep hillside, and grass sod as an undivided “reservation,” perhaps intending to develop the area as a park, although the Company did assert its prerogative to later sell or divide the land as it wished.

(Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna: The Unexecuted Plans For a River City is by Daniel Bluestone and Steven G. Meeks. This article was published in Volume 70 2012 of the Magazine of Albemarle County History by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. Copies of the Magazine are available at www.albemarlehistory.org)

Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna (03)

As agriculture and denser settlement developed along the Rivanna River local residents looked to the river to meet other important needs. The Rivanna provided waterpower to run mills that processed timber, grain, and wool. In many areas, tapping the river’s waterpower required the construction of dams that obstructed the older established patterns of river navigation. In the first third of the nineteenth century, the Rivanna Company and the Rivanna Navigation Company received state charters to undertake improvements, including canals and locks to carry boats around darns and river rapids. Thomas Jefferson’s 1771 hand copy of a survey of the lands of Nicholas Lewis, grandson of Nicholas Meriwether, nicely represents the vision of Charlottesville as a river community. The town and court square stand on the high ground separated by productive agricultural land from the Rivanna. Starting in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century, this productive agricultural land, called The Farm, was taken out of agriculture and became a site for the expansion of Charlottesville settlement. This was also the same area where in 1920 Paul Goodloe McIntire sought to revitalize the connection amongst the town, the people, and the river-in the form of a major riverside park.

The riverside lands had passed through several owners between Nicholas Lewis and developers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. John A.G. Davis purchased large tracts of Lewis’s plantation in the 1820s. Davis commissioned architect Thomas R. Blackburn for a design. He drew upon the talents of builders William B. Phillips and Malcolm F. Crawford who had just finished work on the University of Virginia–to construct a new plantation house overlooking the rich bottomlands along the Rivanna. In November 1840, Davis, a law professor, was shot and killed as he tried to calm a student riot at the University of Virginia. In 1848, William Farish purchased the plantation for his son, Thomas L. Farish, who continued the century-old pattern of cultivating the land. In 1860, the plantation had 300 acres of improved land and 180 acres of forests and meadows. Farish owned 13 horses, 4 mules, 13 milk cows, 4 oxen, 18 cattle, and 22 pigs. In 1860, his fields yielded 15,000 pounds of tobacco, 1,000 bushels of wheat, 2,250 bushels of corn, 50 tons of hay, and 40 bushels of potatoes, while his cows produced 205 pounds of butter. Thomas Farish and his family did not sow or harvest these agricultural products on their own; in 1860, Farish owned 37 slaves who worked his plantation. As a captain in the Confederate Army, Farish fought to preserve this system. At the conclusion of the Civil War, after losing his enslaved labor, Farish began to rent out his land to local farmers.

(Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna: The Unexecuted Plans For a River City is by Daniel Bluestone and Steven G. Meeks. This article was published in Volume 70 2012 of the Magazine of Albemarle County History by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. Copies of the Magazine are available at www.albemarlehistory.org)