At this point the driver has failed to see several signs regarding street usage. Tell them, tell them again, tell them again

Zoning is a tool that legislators use to direct the day to day life in their territory. Zoning can be a glass of water for a thirsty person or club against the head of an enemy.

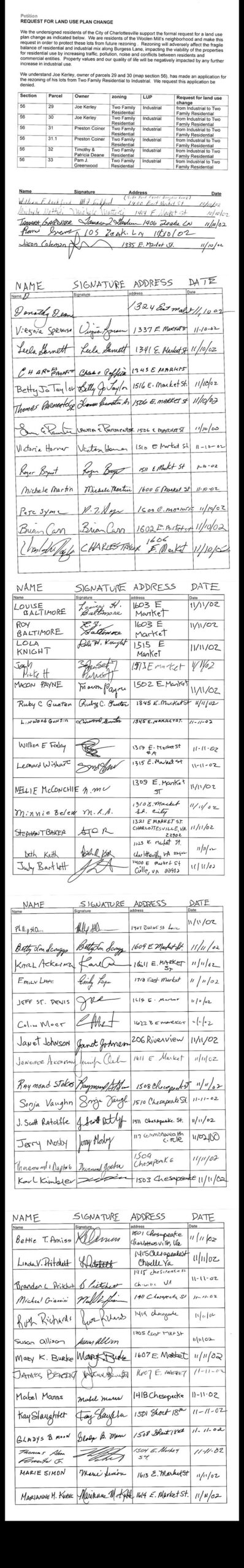

For 40+ years, neighbors have corresponded with legislators and folk in Government about Woolen Mills zoning. This year, an advisory board member responded (thank you Lyle) but otherwise, no member of the City Council, of the deciders, has chosen to engage us in conversation.

In 2000, for the Comprehensive Plan, NDS came to the neighborhood and requested input. It was a different era.

This post is a cursory examination of zoning when used without the consideration of The People whose neighborhood will be shaped by the zoning. We are interested in why zoning practice is repeatedly bad zoning practice. We interact and interact and little changes.

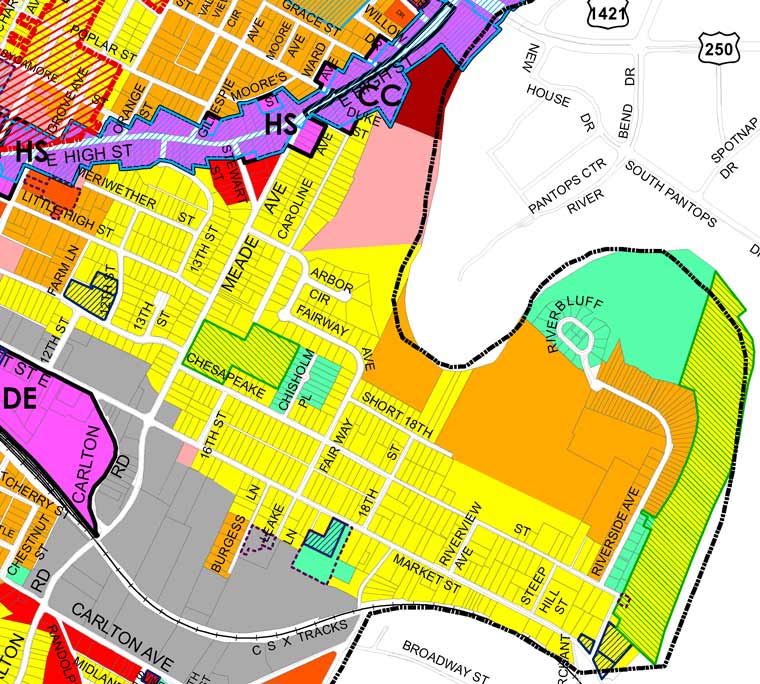

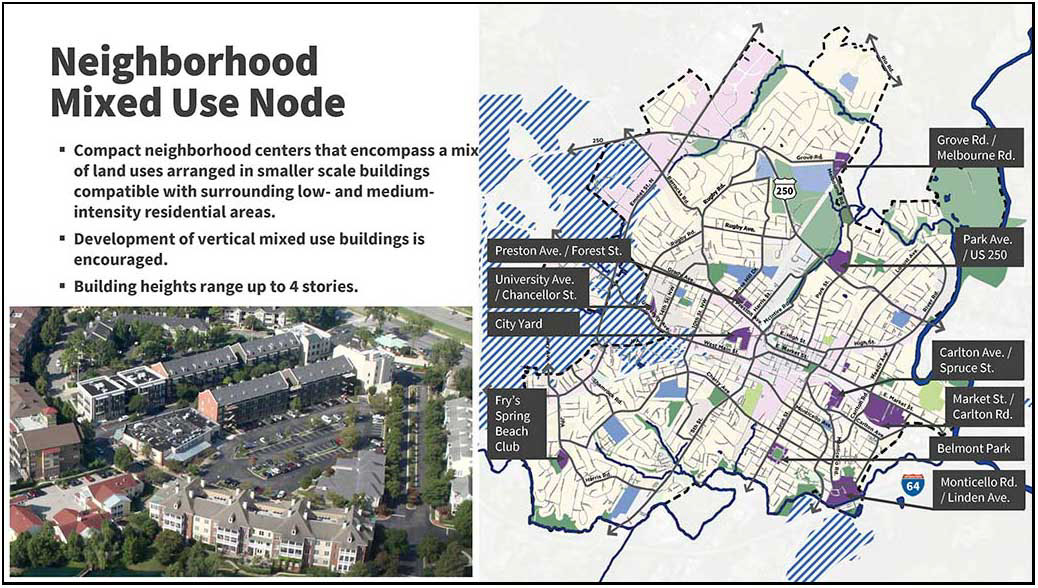

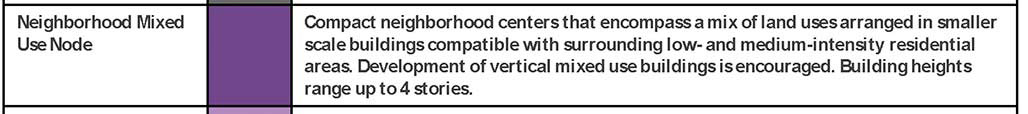

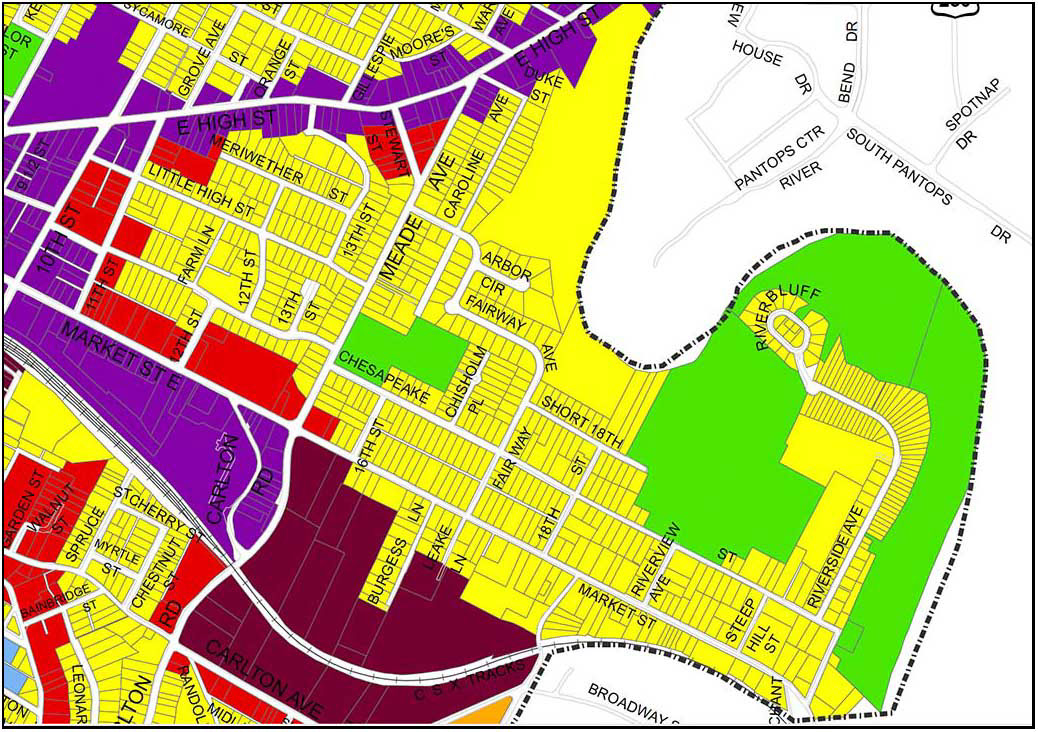

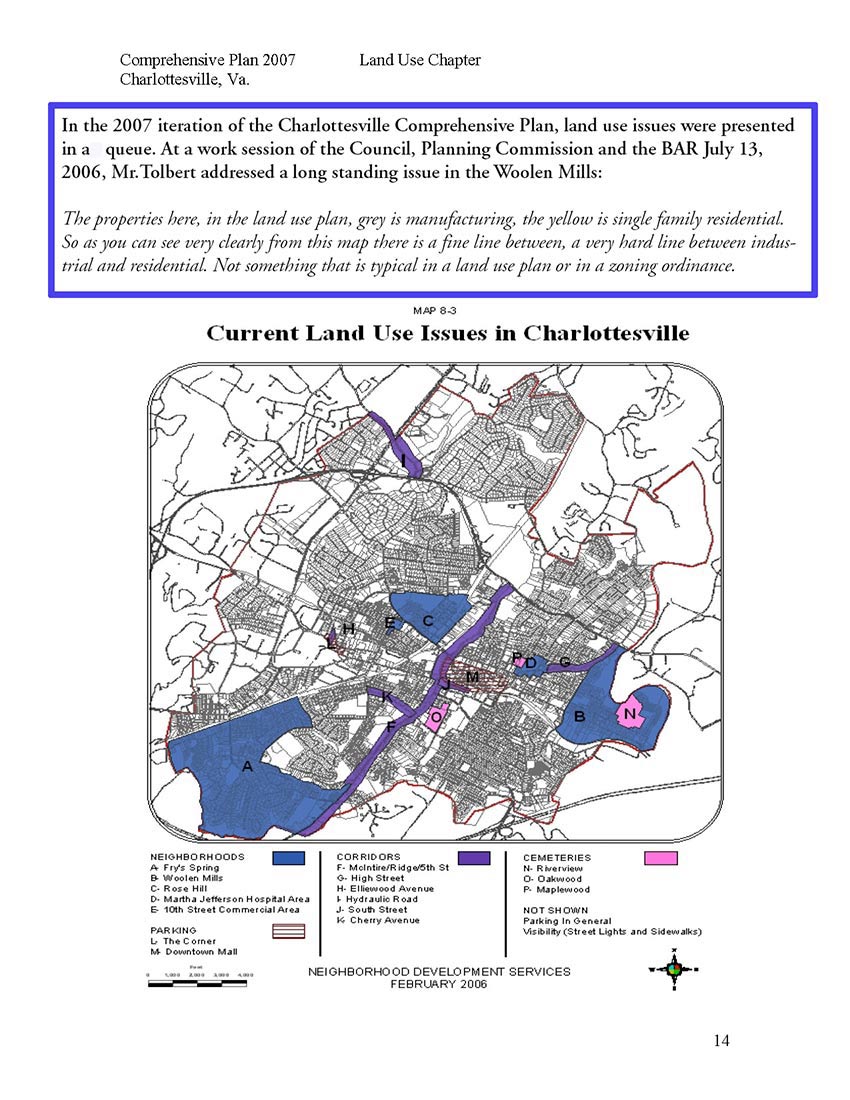

Mr.Tolbert on the “very hard line between industrial and residential.” Now the hard line is between IX-5, NX-3 and residential. Carrying forward the vision of Council from 1957.

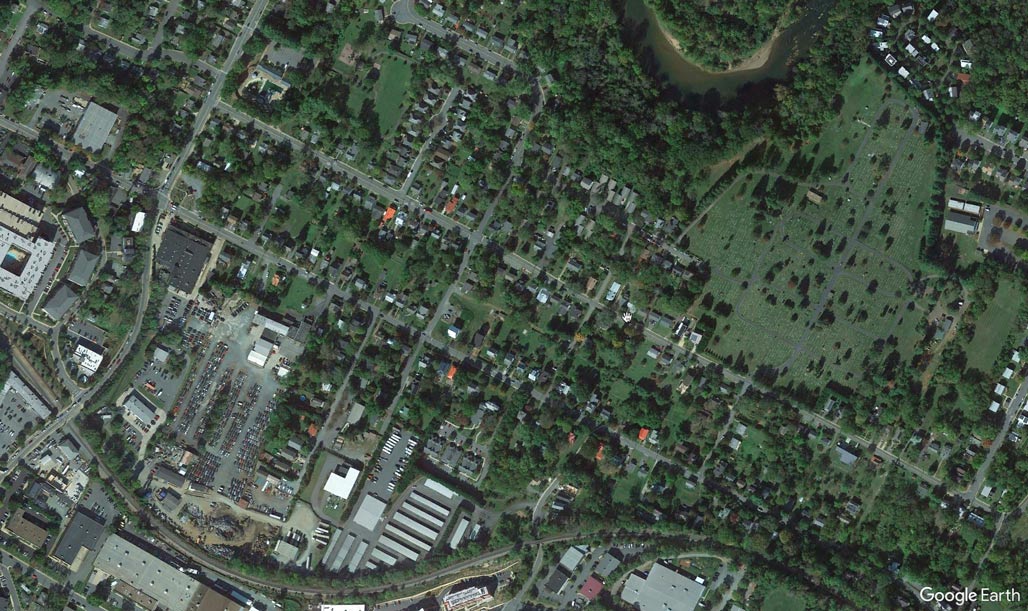

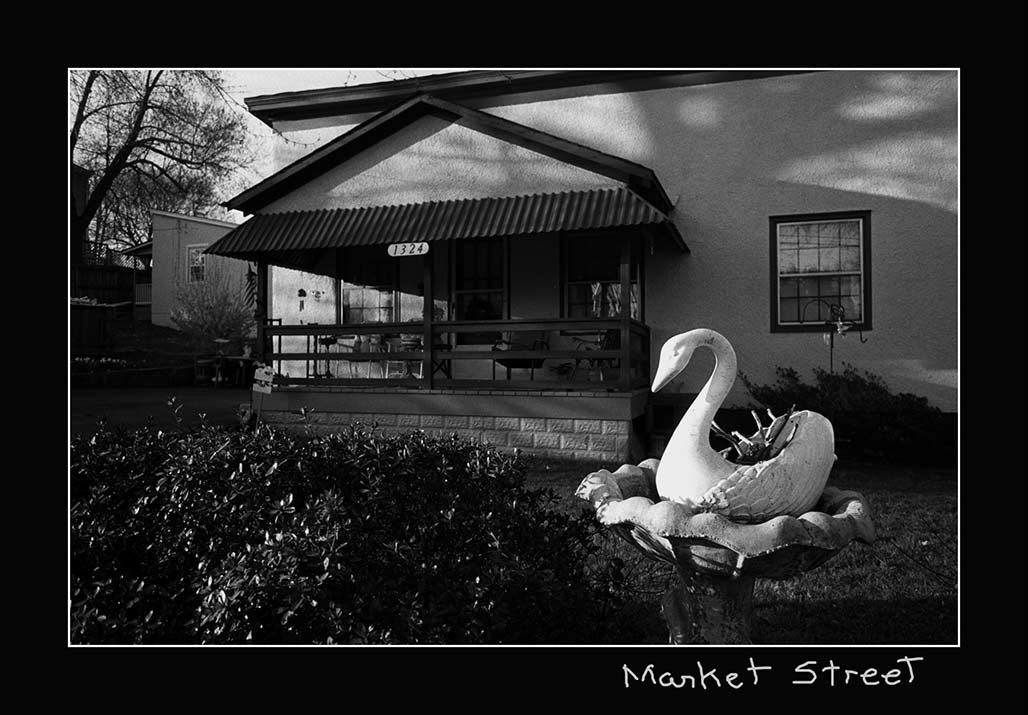

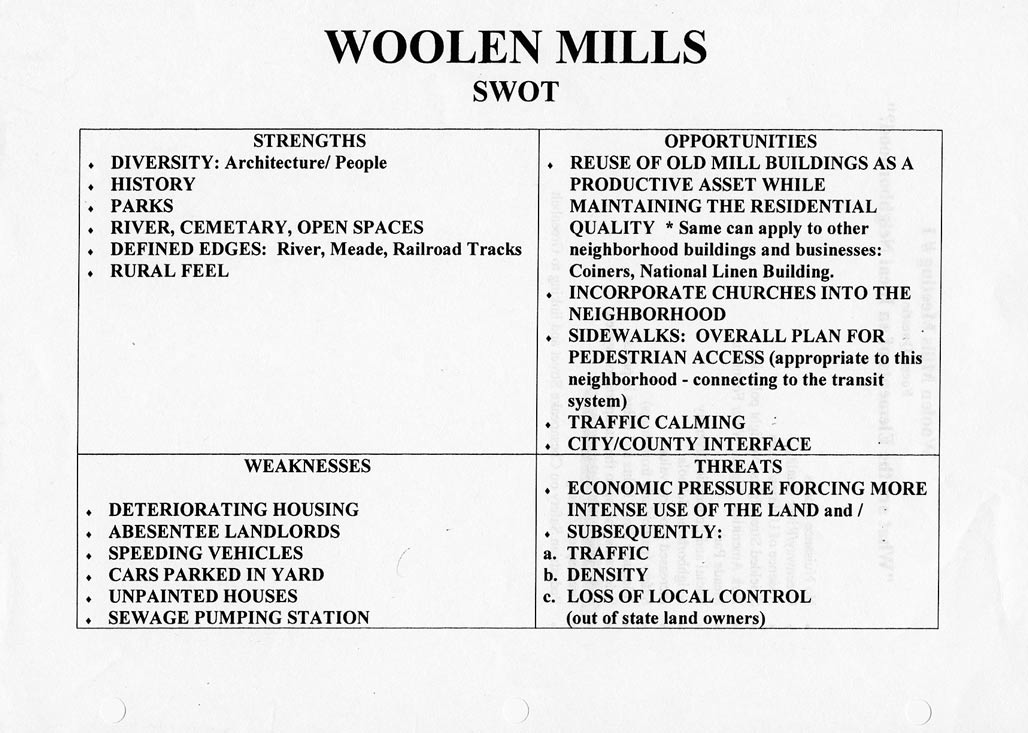

A neighborhood is a living thing composed of topography, culture, people, plants, pathways, businesses, animals and architecture. Neighborhoods require planning and care. It has been So Discouraging trying to obtain planning and care from our City. Neighborhoods are sensitive.

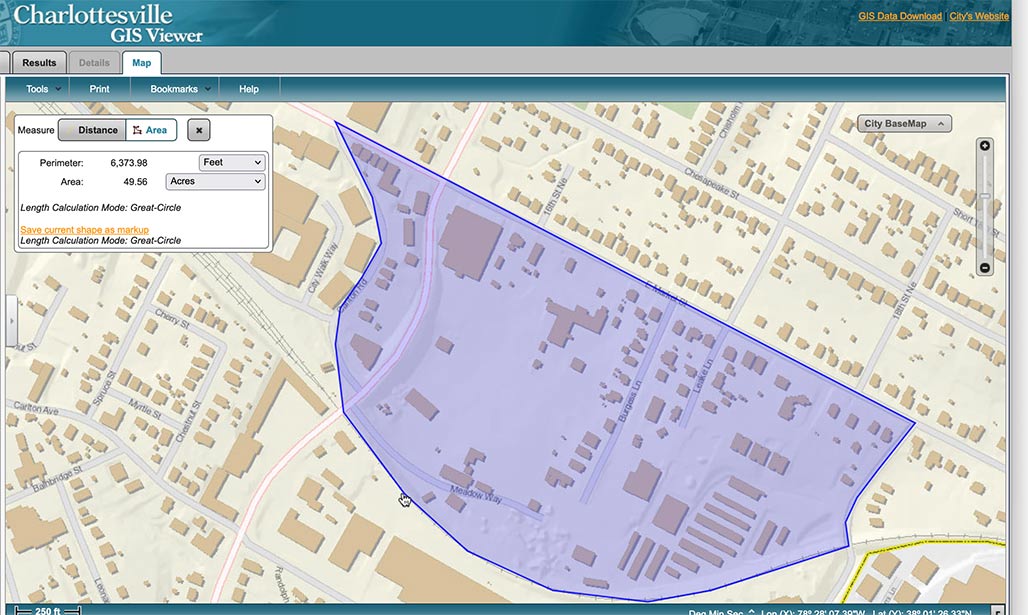

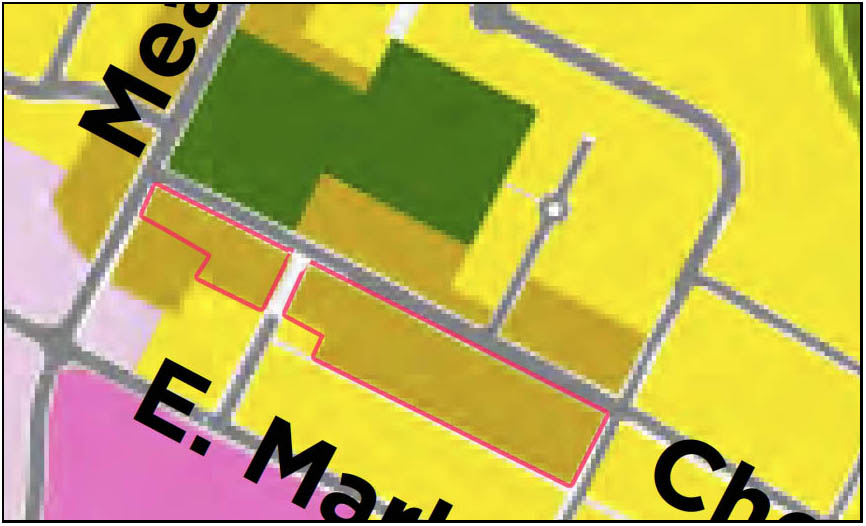

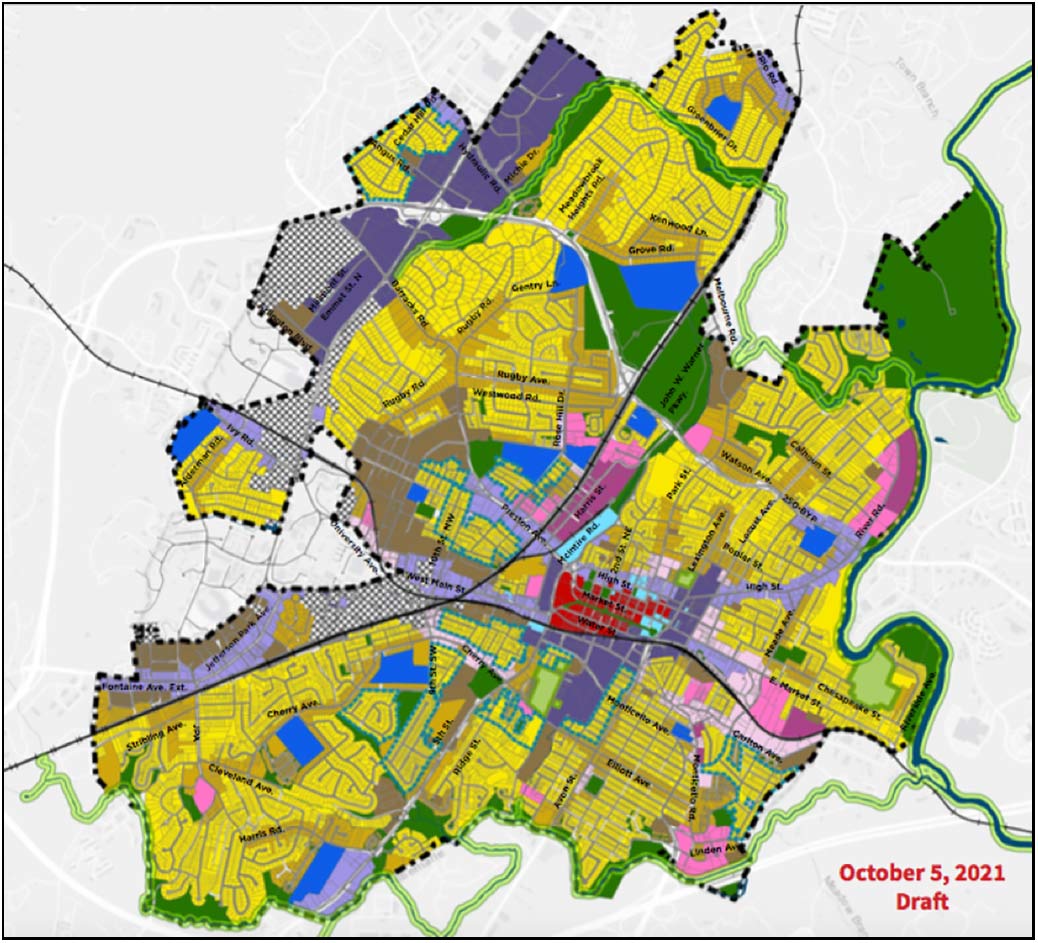

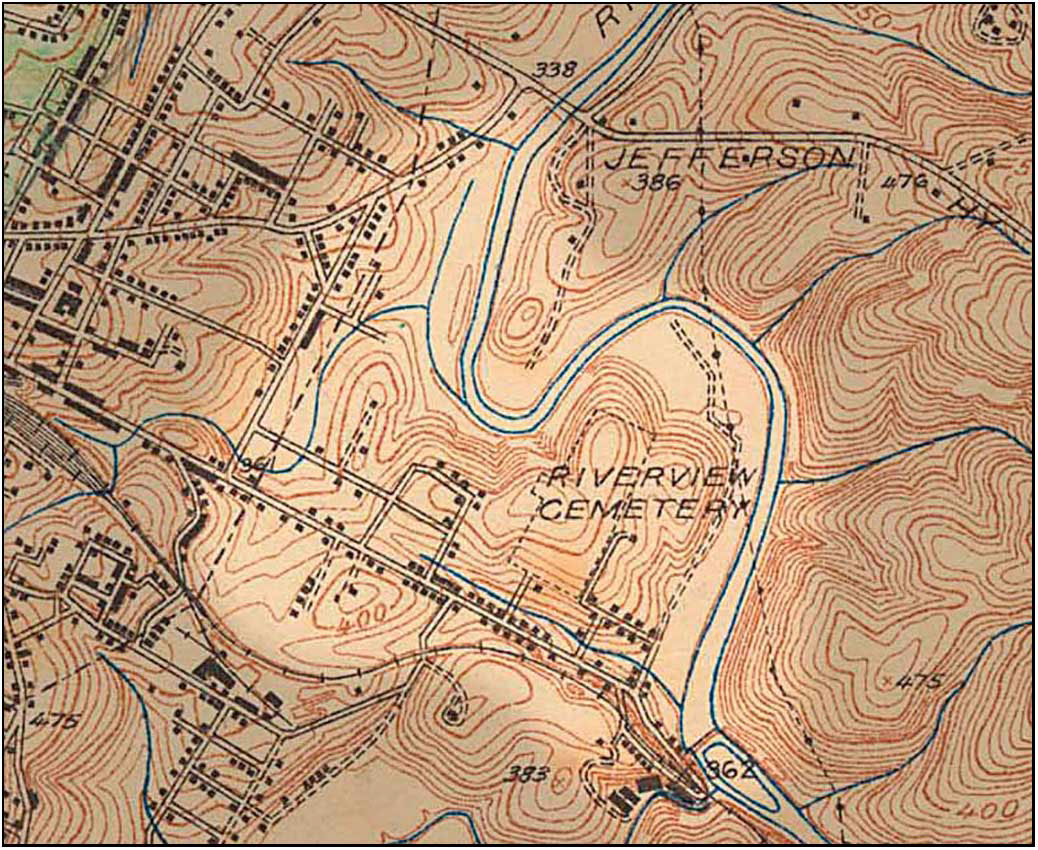

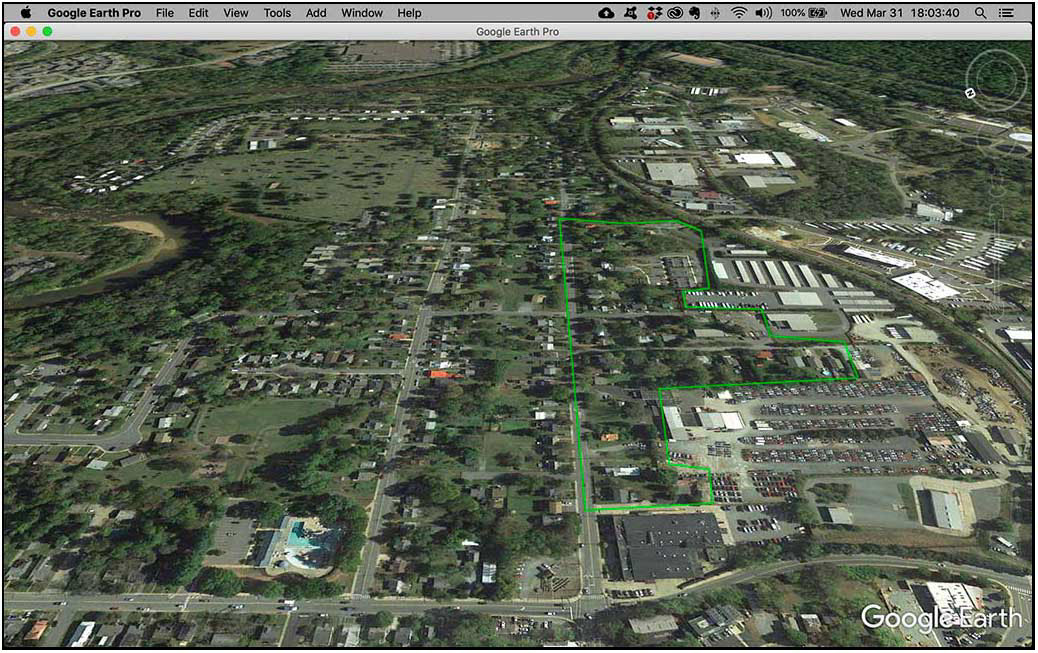

The land affected by split parcel zoning lies in the area of the Woolen Mills between Carlton Road and Franklin Street. It is the land north of the C&O railroad tracks and south of East Market. This acreage has been the seed for multiple conflicts in the past 35 years.

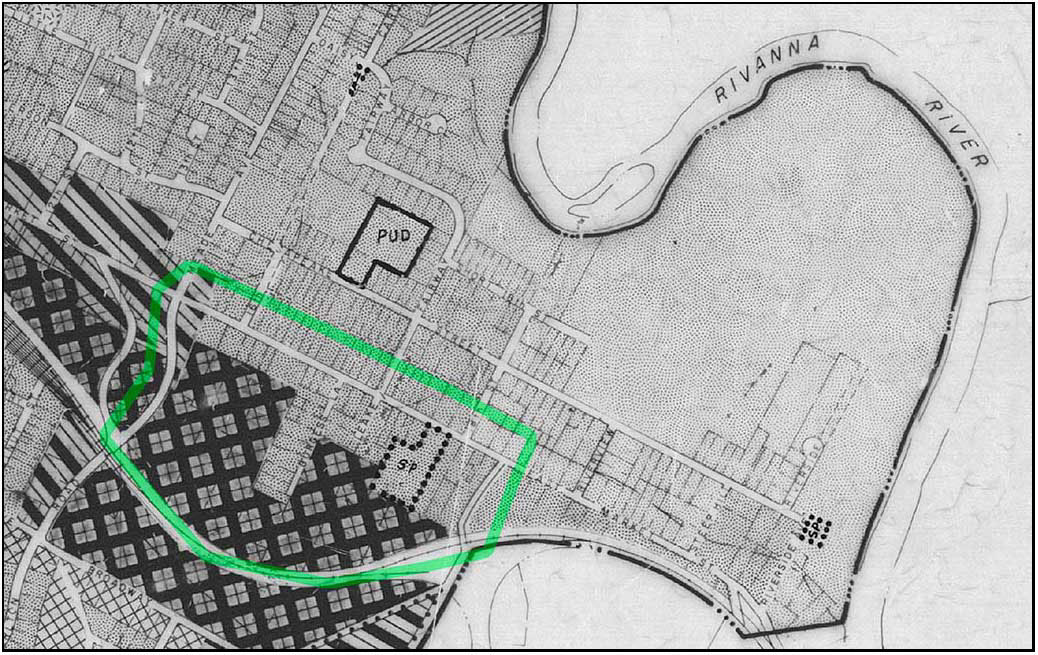

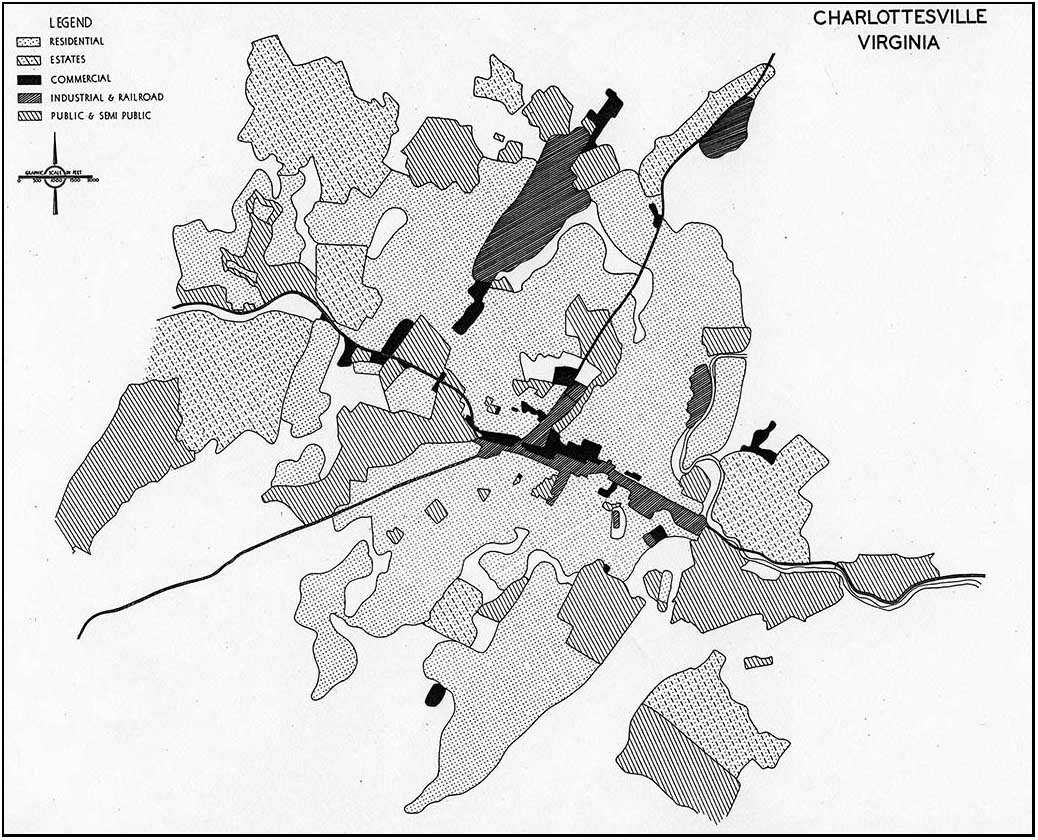

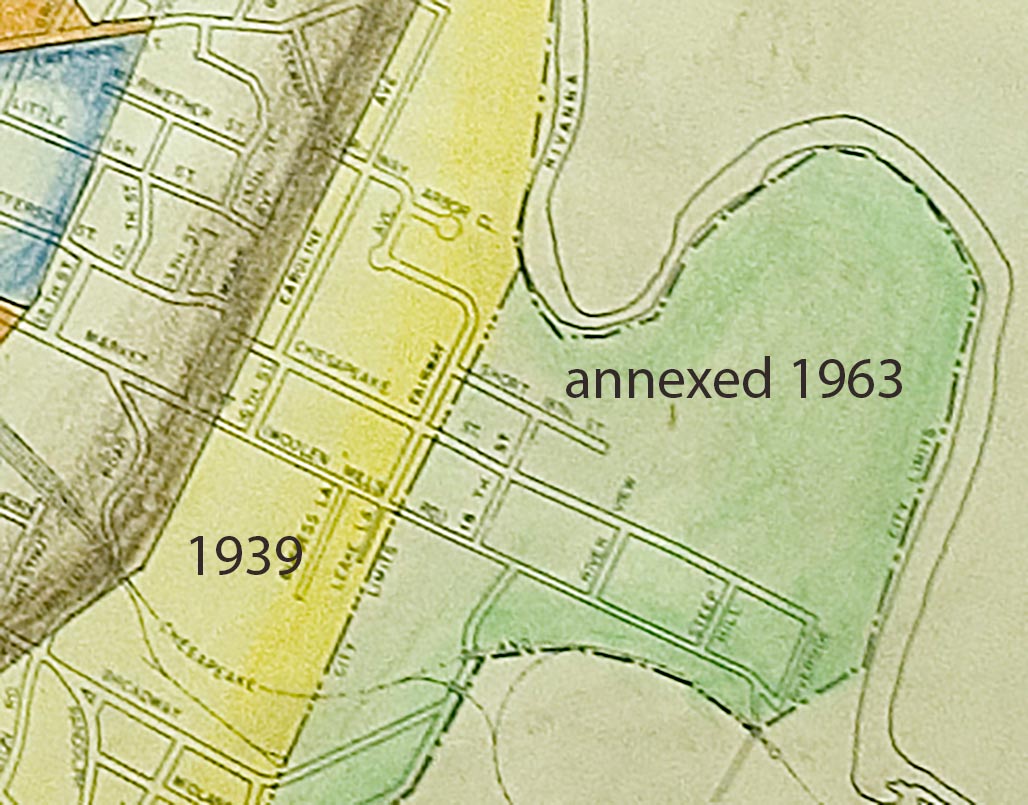

7 years before the annexation of the area in eastern Woolen Mills and Harland Bartholomew and Associates has a plan to line the south side of Market all the way to the Rivanna with Industrial.

In the beginning, In the 1950’s, around the time that Council approved Harland Bartholomew’s “Workable Program for Urban Renewal” they looked down the road with guidance from HBA and made decisions regarding future zoning of Woolen Mills backyards.

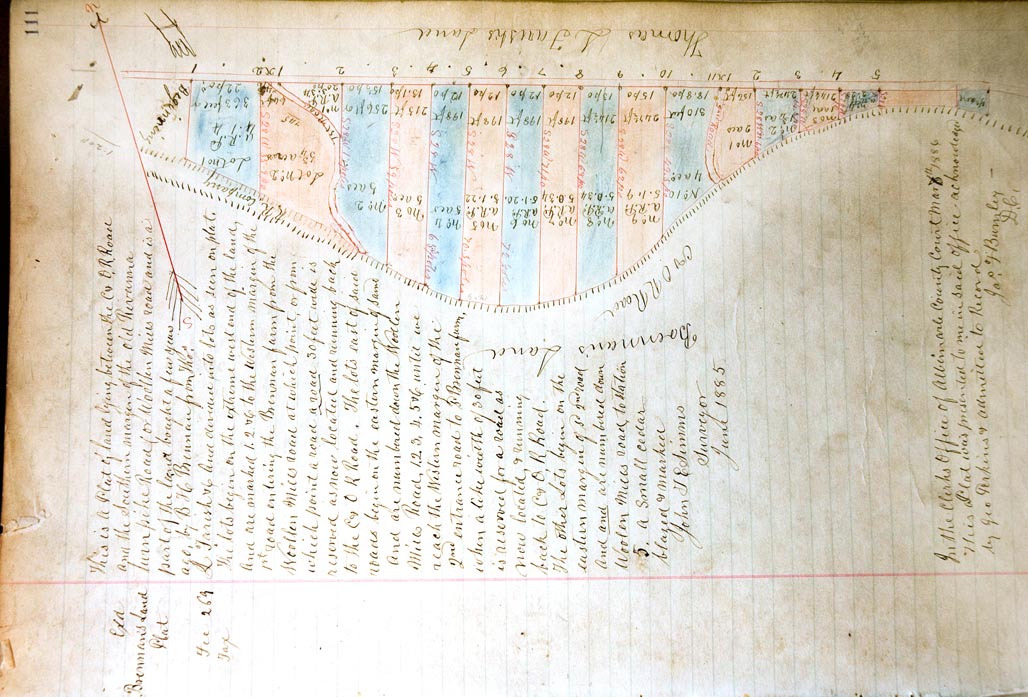

AlbCo adopted zoning in the late 1960s (1969?) Zoning wasn’t a concept familiar to Woolen Mills people, planning for the zoning was done to them in advance of the 1963 annexation. We are not aware of a public process.

This is the region of split parcel zoning, residential in the north, industrial in the south.

With the passage of the decades the green residential boundary bordering the southern edge of Market Street has gradually been eroded.

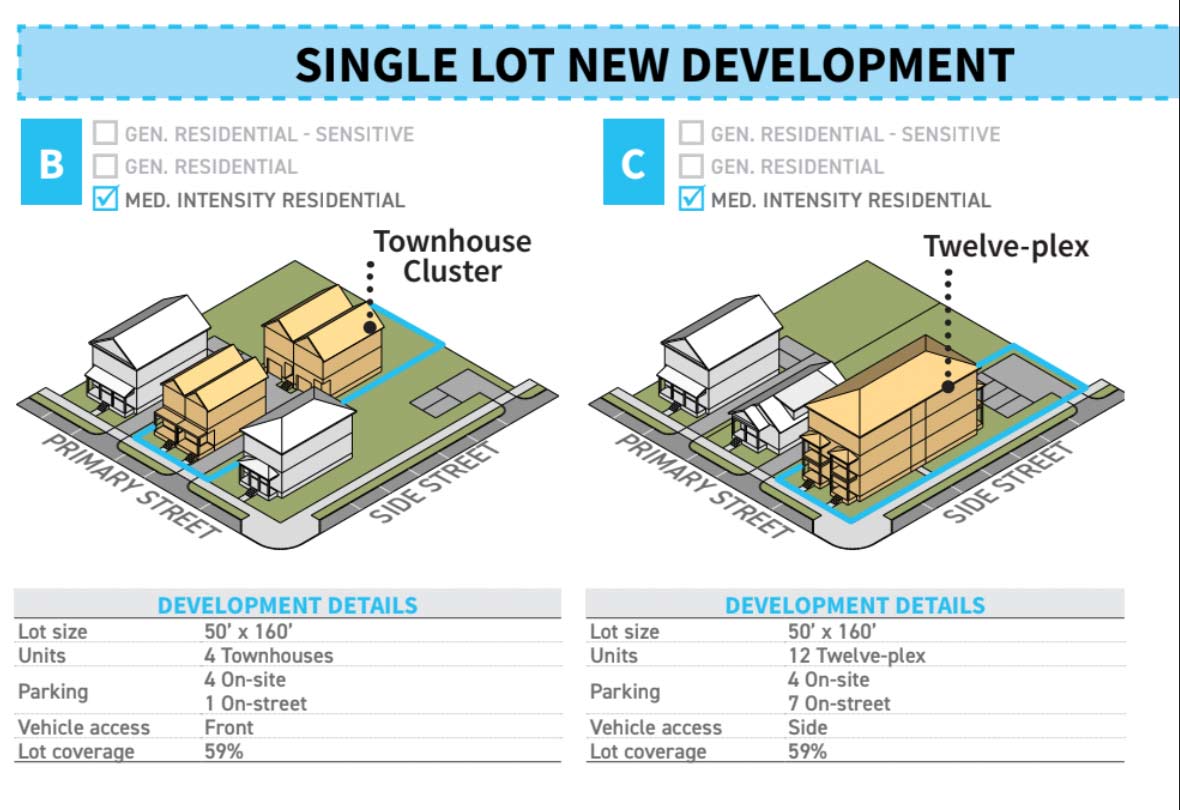

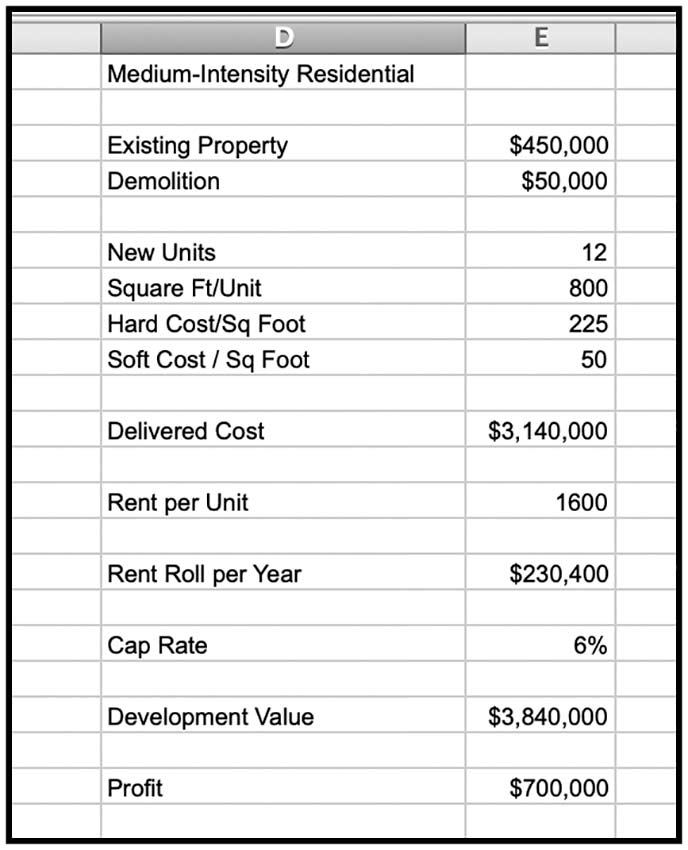

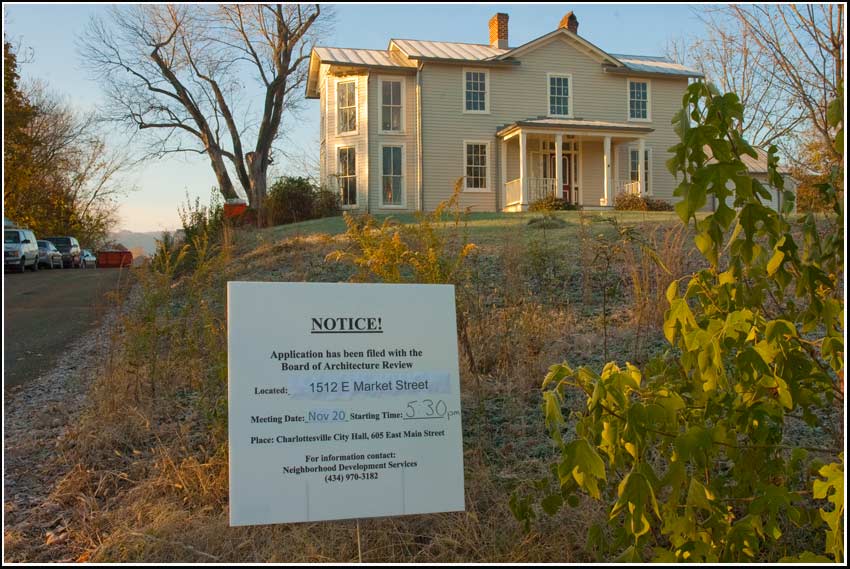

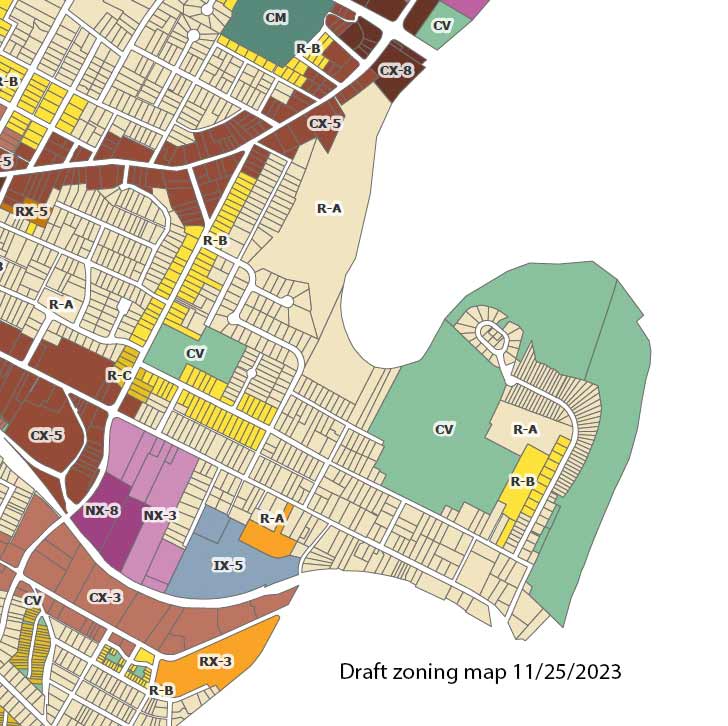

The proposed zoning map removes another 390 feet of the residential gateway to the neighborhood on the south side of Market. For decades we have fought lot by lot to determine the zoned future of the WMN.

The current Council expresses the intention to remediate the damage done by their predecessors in the 1950s in selected neighborhoods. I wish that Council would act with an awareness that the damage of HBA’s planning advice extended beyond Charlottesville center city.

The split parcel zoning, residential contiguous to industrial, has resulted in numerous land use conflicts over the decades. Thousands of staff and resident hours have been invested in addressing the incompatible zoning district pairings in PUD, SUP, rezoning and BZA public hearings. There have been zoning violations and lawsuits. Neighbors have breathed particulates, smelled stink and been exposed to debilitating noise.

The proposed zoning map needs adjustment in the Woolen Mills neighborhood.

1-pause the proposed Woolen Mills R-B zoning to avoid displacing current residents and motivating the destruction of modest homes. Talk to those who will be affected!

2-abide by the mapping logic and hold with NX-3 zoning instead of NX-8 for the Wright’s property. No ten story buildings at present!

3-Complete the Small Area Plan (SAP) formally requested by Joe Rhames on behalf of the Woolen Mills in August 1988 before up-zoning Woolen Mills residential properties beyond R-A.