At Pantops, Mcintire was attentive to the vestiges of a prior institutional landscape and a set of buildings that could be adapted for the treatment of patients with mental illness. In 1877, Reverend Edgar Woods had purchased 373 acres at Pantops and opened Pantops Academy, a boys’ preparatory school, with close connections to the University of Virginia.

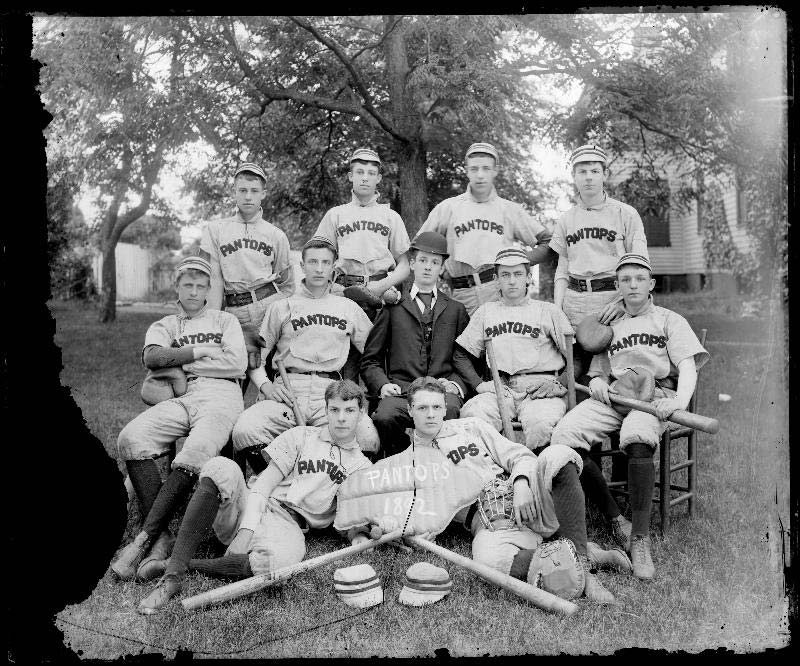

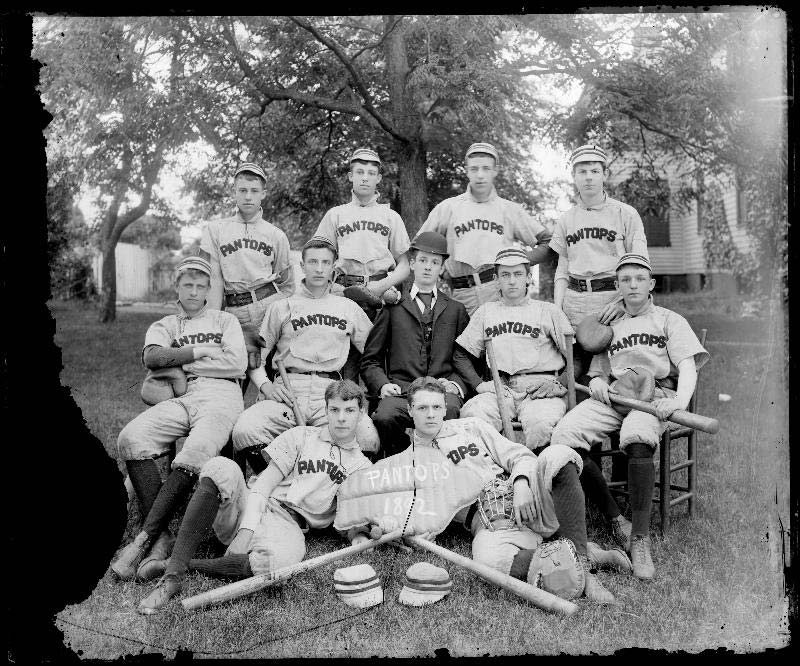

UVA Special Collections Pantops Academy

The Academy promoted the healthy, uplifting, character of the site–a setting and a rhetoric that could have easily been adapted from education to healing patients. In 1894, the Academy catalog declared, “The place formerly belonged to Thomas Jefferson, and is on the hill opposite his home, MONTICELLO. Its name was given by him for two Greek words, meaning ‘All seeing,’ in allusion to the prospect, which embraces the town of Charlottesville, the University of Virginia and a wide extent of plain and mountain scenery, not excelled by any other portion of the land. The surrounding region is one of the most healthy which the country contains, and is absolutely free from every kind of malaria …. It is scarcely possible to emphasize too much the unsurpassed location of the Academy, which not only delights the eye with the wide range and beauty of the landscape, but which ensures the best sanitary conditions, through perfect drainage and purest mountain air. Its distance from Charlottesville secures it from town temptations.” The Pantops Academy drew much of its food from its own farmlands declaring, “The teachers and pupils live together as one large family. The table is largely supplied from the farm, thus commanding abundance of milk and cream from its own dairy, fresh vegetables and fruit from its own garden and orchard and its fresh meat from its own flocks.”

Baseball team, Pantops Academy, 1892. University of Virginia, Holsinger Studio Collection

The Academy provided an indoor gymnasium but insisted that the site itself, with its elevated views, its hills, pastures, gardens, and river would provide for the healthy “physical culture” of the students with the “large grounds and the ample range the country thus affords.” Even though the Academy had closed in 1904, the prominent dorm and classroom building, built in 1884, and the rambling principal’s residence still dominated the site. Mcintire could imagine that they would be easily adapted for a psychiatric treatment hospital. Essentially what Mcintire could see in Pantops was what he had seen in the possibilities of a Rivanna public park–a landscape that would provide comfort and engagement and continue to cultivate the vital historical relationship between people in the region and their river.

Rivanna at Riverview Park. Montalto in the distance.

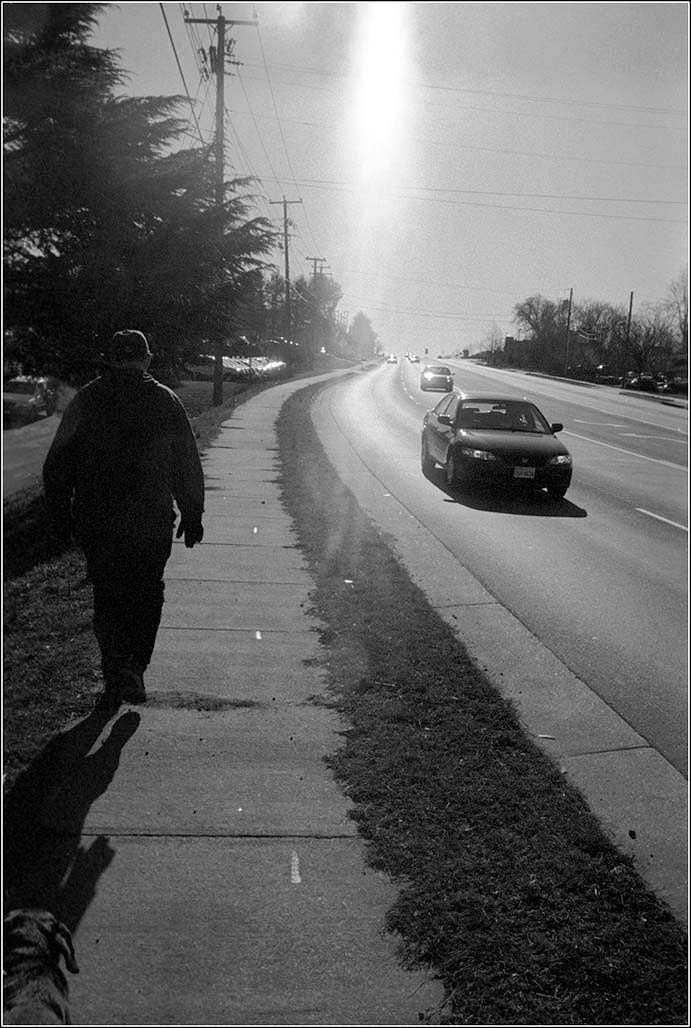

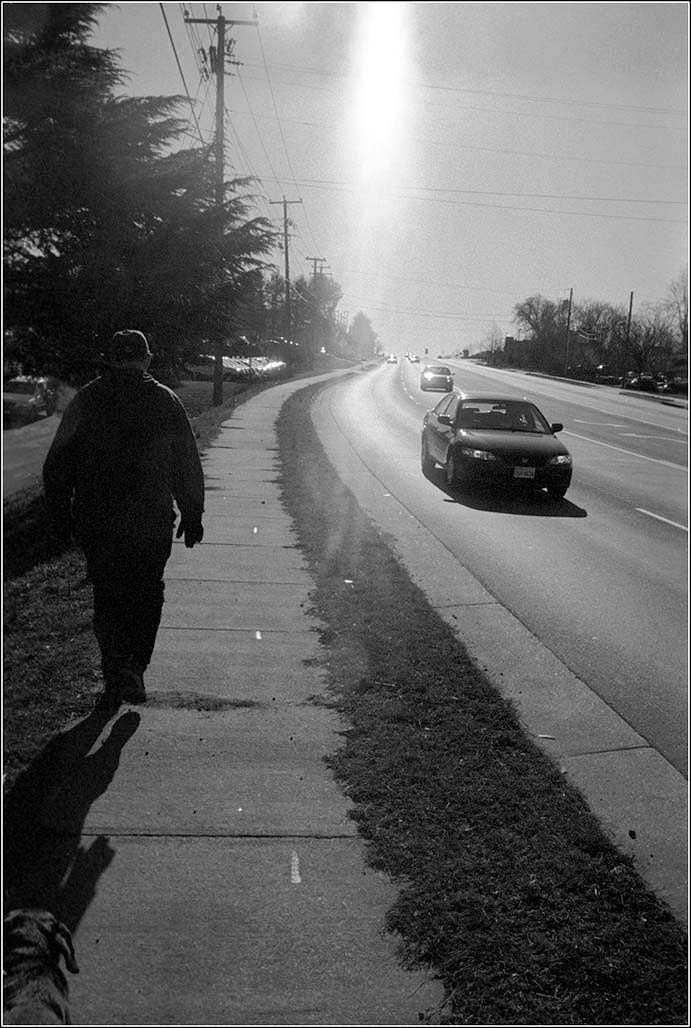

It was only a matter of months between Mclntire’s Pantops purchase in July 1929 and the crash of the stock market. In the midst of the Depression, the University was not able to expand to Pantops, and in 1937 the University’s Board of Visitors resolved to sell Pantops to James H. Cheek for use as a private country estate and horse farm. The proceeds of the sale were devoted to the development of psychiatry at the University hospital. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, Pantops was divided for private residential and commercial developments. State Farm Insurance opened a regional headquarters on part of the land in 1979. The Pantops Shopping Center opened in 1984. The Westminster Canterbury Retirement Community opened in 1990 and the new Martha Jefferson Hospital moved to Pantops in 2011. By 2010, Free Bridge carried an average of 38,000 cars a day over the Rivanna between Pantops and Charlottesville; however, the automotive landscape that gripped the river and determined adjacent lands uses did little to connect people to this particular and special place or to the Rivanna itself, with its rich historical, cultural, and environmental resources.

Sidewalk to the summit.

Mclntire’s vision for the Rivanna embodied a complex ideal concerning the proper relationship between the Rivanna, the broader development of the city, and the citizens of Charlottesville. Interestingly, the person who enacted part of this vision in the wake of Mclntire’s failure was John Wesley Bagby (1888-1968), a life-long employee of the Charlottesville Woolen Mill, who labored initially as a mill hand and became the superintendent of the dye works. In 1928, Bagby purchased 23 acres of the Albemarle Golf Club lands along the Rivanna for $3,000. Around 1940, Bagby began using his land as a site for periodic circuses and carnivals. This tradition lasted for half a century. When the three-ring Barnum and Bailey circus visited in 1954, the enormous circus tent pitched on the banks of the Rivanna, just south of Free Bridge, would accommodate 10,000 spectators who came to see elephants, tigers, clowns, and high-wire gymnasts perform. Here was a vision of a city gathering along the river for amusement, entertainment, relaxation, and neighborly socializing. But even these events only took place periodically.

Bagby’s Circus Grounds 2014

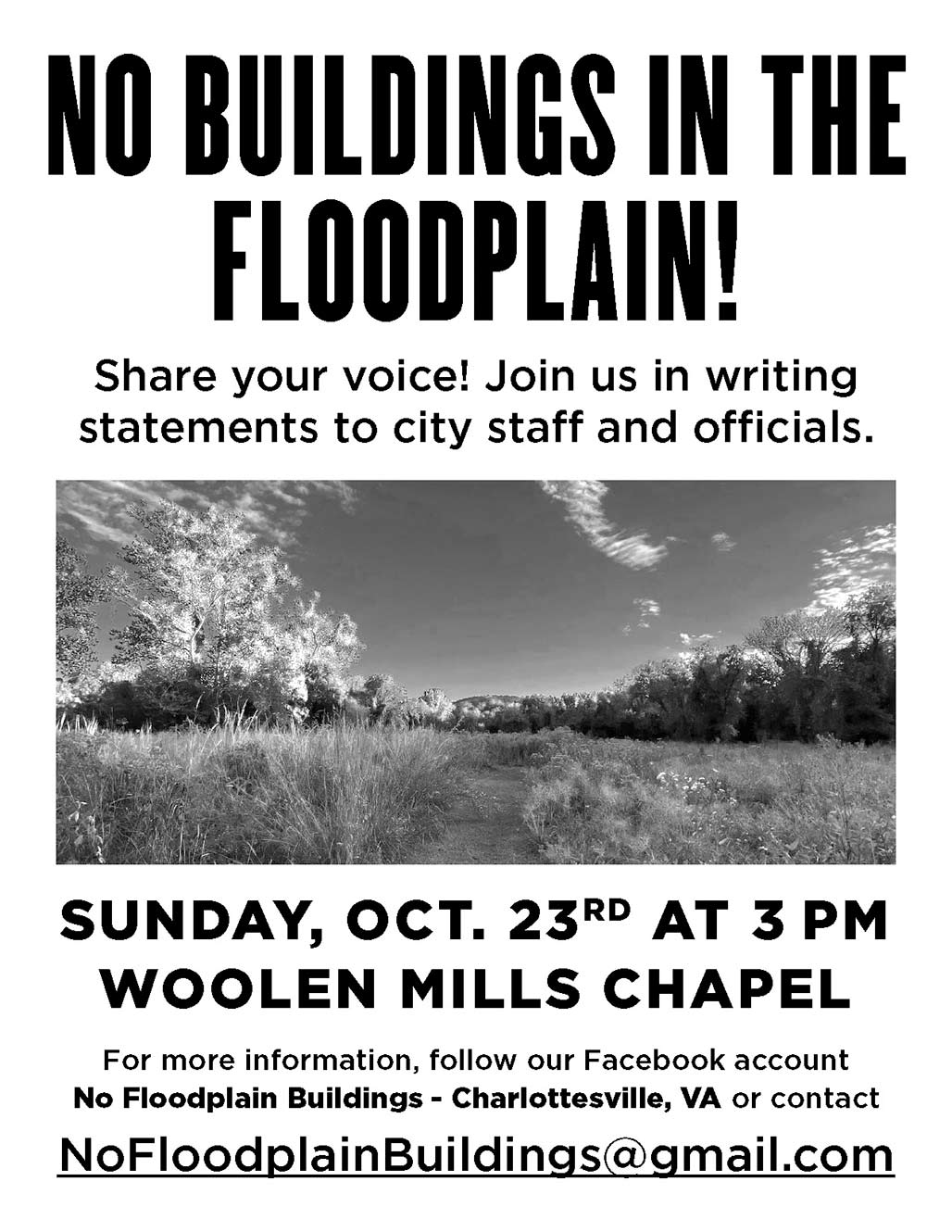

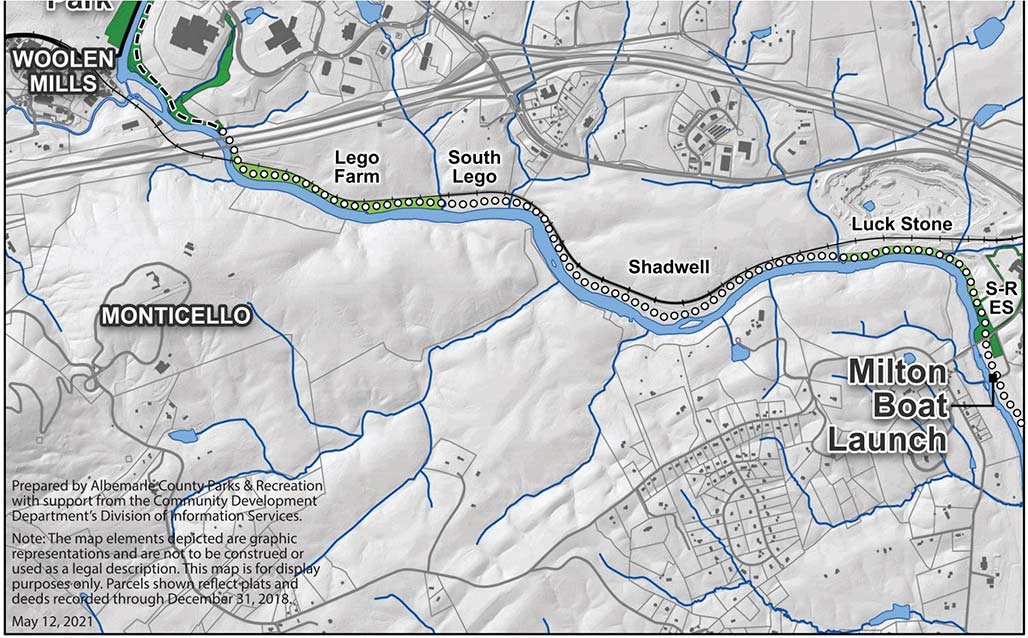

The rising national environmental movement began to frame local connections to the Rivanna from the 1960s onward. The Virginia Assembly passed the Scenic River Act in 1970; the Act required that scenic values be considered in public planning decisions around designated scenic rivers and established regulations to prevent the construction of dams that impeded the flow of water on scenic rivers. The section of the Rivanna River in Fluvanna County was designated in 1974, and the designation was moved upstream to the dam at the Charlottesville Woolen Mills in the late 1980s and to the South Fork Reservoir Dam in 2009; this later designation was granted after the Woolen Mills Dam was removed in 2007 to promote the ecological health of the river and its fish population. The opening of a jointly purchased city-county park in 1986, now named Darden Towe Park, prompted a series of initiatives in the 1980s and 1990s to open trails along the Rivanna with legal easements over privately held property. The trails now amount to ribbon parks and are popular for outdoor exercise, walking, running, and biking.

Birders

The environmental focus on the Rivanna River is a much narrower vision than Paul Goodloe Mcintire had tried to effect. When Charles Hurt filed plans for the Pantops Shopping Center in the 1980s, people advocating for the Rivanna’s ecology opposed the plan, worrying about pollution, run-off, and flooding. The Rivanna represented a problem and a threat for the Pantops Shopping Center development. The Center ended up being constructed with its back to the Rivanna, largely disengaged from the river.

Mclntire’s failed 1920s plans for connecting the city and the Rivanna represented a more complex integrated vision that reflected the historical realities of the river’s significant place in the region. The vision saw people living, working, recreating, and being healed in a landscape that intermingled human artifice with a key environmental and cultural system-the Rivanna River. In the early twentieth-first century, the Rivanna is part of many people’s lives in the region. When they turn on the tap in their sinks, water arrives from the South Fork of the Rivanna River. When their streets and houses shed rainwater, or when they flush their toilet, they send away liquid waste that eventually ends up in the Rivanna. And yet relatively few people really experience, know, or understand the Rivanna River. The rise of the single purpose planning, for recreation, water supply, sewage disposal, transportation, and housing has exacerbated this reality. When Mclntire’s vision for the Rivanna failed, many citizens in Charlottesville lost sight of their history and their river.

The Rivanna behind Riverbend Shopping Center

Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna: The Unexecuted Plans For a River City is by Daniel Bluestone and Steven G. Meeks. This article was published in Volume 70 2012 of the Magazine of Albemarle County History by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. Copies of the Magazine are available at www.albemarlehistory.org