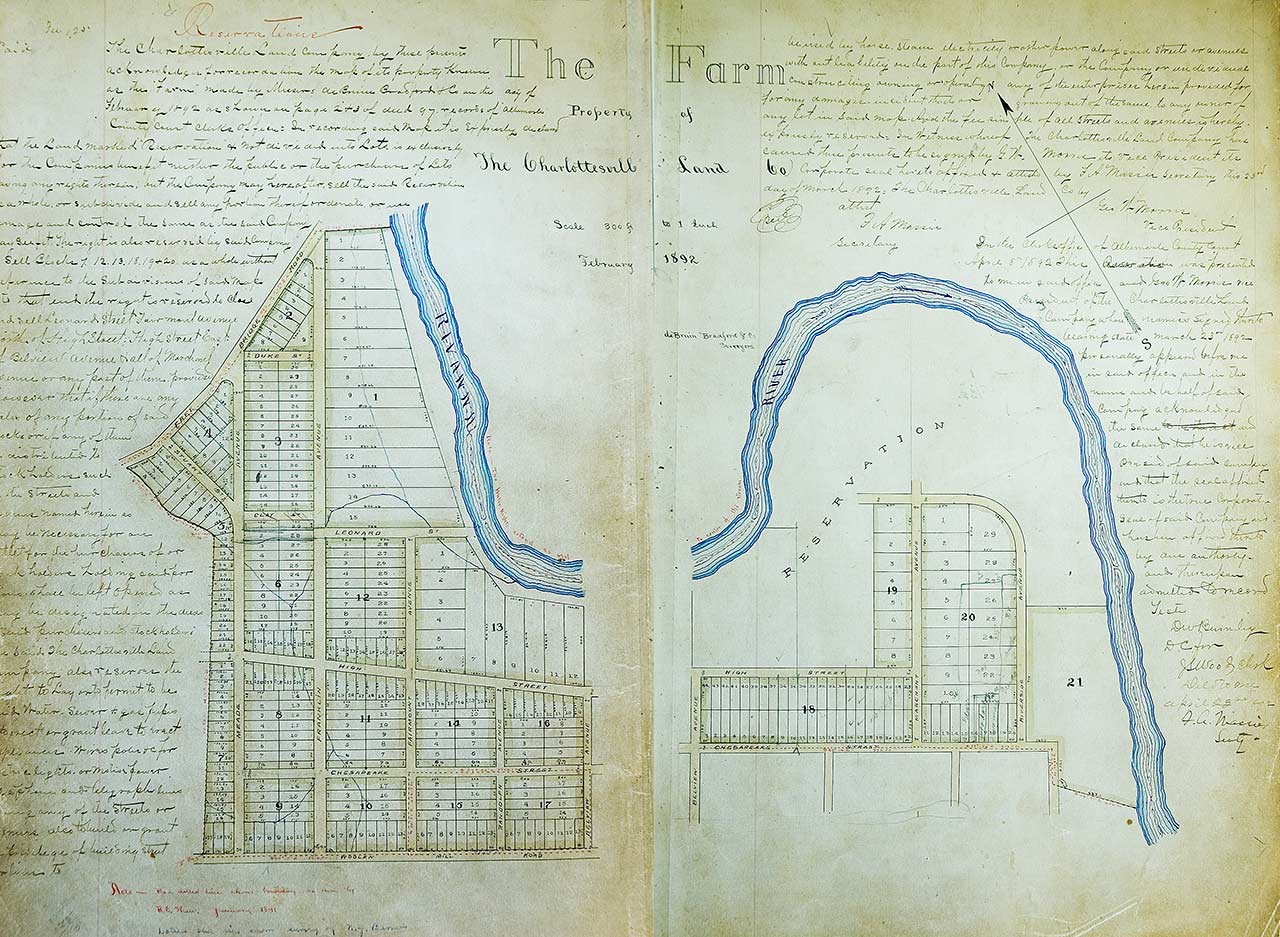

In 1915, five years after Henry Clay Marchant’s death, his heirs turned the riverside land over to a group that saw in it a great aesthetic and recreational resource. The heirs leased, and later sold, the Marchant tract to the Albemarle Golf Club. Established in 1914, the club had enjoyed rapid growth, initially using leased land on Rose Hill. In 1915, George R. B. Michie, a charter member of the club and the president of the People’s National Bank, approached the Marchant heirs and worked out a three-year lease for their land along the Rivanna River. For Michie, the arrangement seemed ideal. In 1909, Michie and his family had taken up residence in the 1820s house built by John A. G. Davis as the plantation house of The Farm.

The house continued to look out over sod and pastures that the Marchant family had maintained since the 1890s. Now, with only minor changes, the landscape character would be preserved, and Michie would have the added advantage of having a golf course adjacent to his residence. For their part, the Marchant heirs insisted on preserving the pastoral character of the site. Their lease called for the land to be used for “athletic and grazing purposes only, and shall not be cultivated except so far as is necessary to get said land in the best condition possible for the raising of grass and sodding said land.” The sod could be removed only to build tennis courts and putting greens, and would have to be restored at the end of the lease. The existing grade of the land could not be altered, and no trees could be felled, save for a small orchard that could he removed if the golfers desired.

The rising popularity of golf in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was directly tied to the perception that urbanization would erode the health and vitality of the American citizens. A growing number of people who had been raised in the outdoors, on rural farms, had now taken up residence in cities and were spending their working lives indoors. This fact made the golf course seem an especially attractive venue for such city-dwellers to ensure healthy and restorative leisure. Pointing to the new golf course along the Rivanna, the Daily Progress reported: “The new grounds are within a short walking distance from the business center of Charlottesville ….The club is meeting a long-felt want in this community-that of furnishing healthful outdoor exercise for business and professional men who are kept in store or office during the major portion of the day.” Many charter members of the Golf Club did indeed spend their days indoors doing white-collar work. For example, George Michie worked in the People’s National Bank at Third and Main. Marshall Timberlake ran his pharmacy at Fourth and Main. W.J. Keller and Harry George operated their Main Street jewelry shop between Second Street and Third Street. All of these men lived within a few blocks of their workplace . All could now golf along the Rivanna where tennis, baseball, and boating were also available. Clearly, the Golf Club represented a new use for the agricultural lands along the Rivanna. Indeed, despite the appearance of the land that seemed somewhat pastoral in nature, the Marchant heirs had forbidden the planting of corn on the site and in 1915 after a “very rigorous debate,” club members voted to terminate the pasturage of cows on the land, preferring to pay for the mowing of the fairways. Under these changed circumstances, the agricultural landscape grew increasingly attenuated; nevertheless, with the introduction of golf, the site retained both its alluring pastoral character and its intricate connection to the economic, residential, and social life of the region. In 1918, pleased with their location and the growth of their organization, the Albemarle Golf Club paid the Marchant heirs $18,800 and took full ownership of their riverside golf course.

Members of the Albemarle Golf Club, 1921. Although not pictured, women could join the club as non-voting members, paying half the annual membership fee of men while the entrance fee was waived. Photo courtesy collection of the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society.

Paul Goodloe McIntire’s Rivanna: The Unexecuted Plans For a River City is by Daniel Bluestone and Steven G. Meeks. This article was published in Volume 70 2012 of the Magazine of Albemarle County History by the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. Copies of the Magazine are available at www.albemarlehistory.org