This is a tale about the 22 houses on the left. The 1300 block of Chesapeake Street.

The lots are long and skinny, they are zoned R1s, they are intended for residential use.

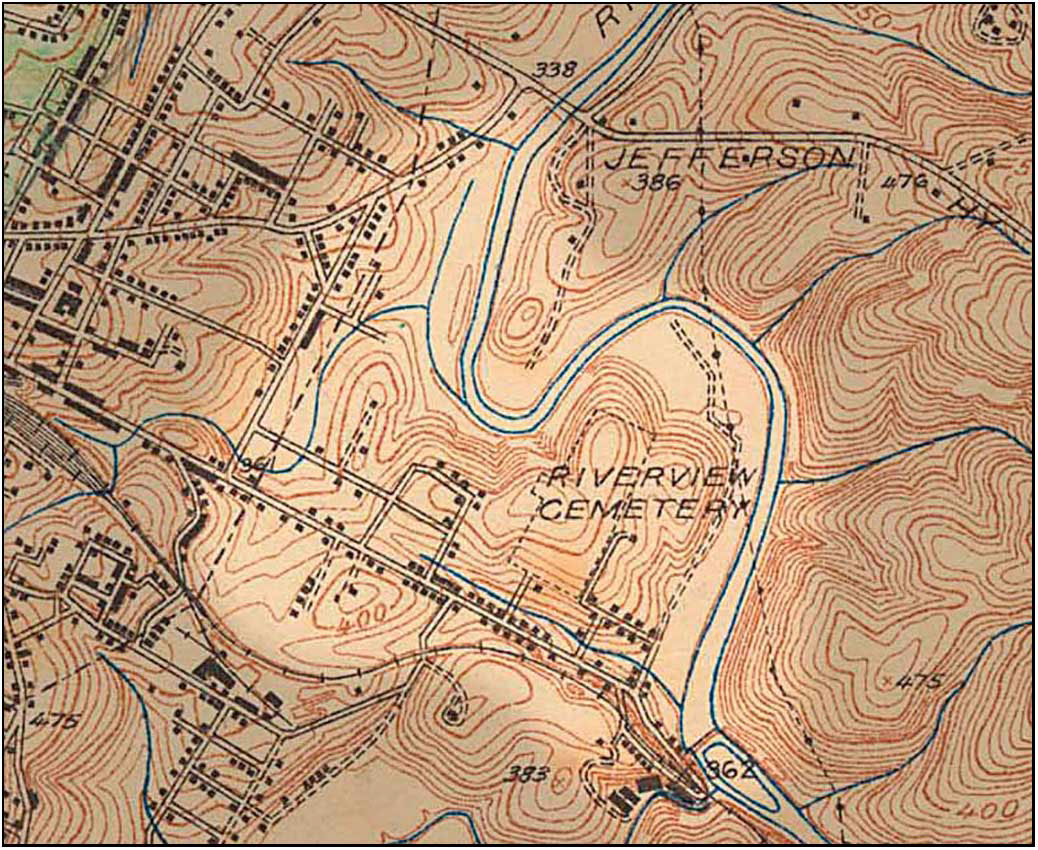

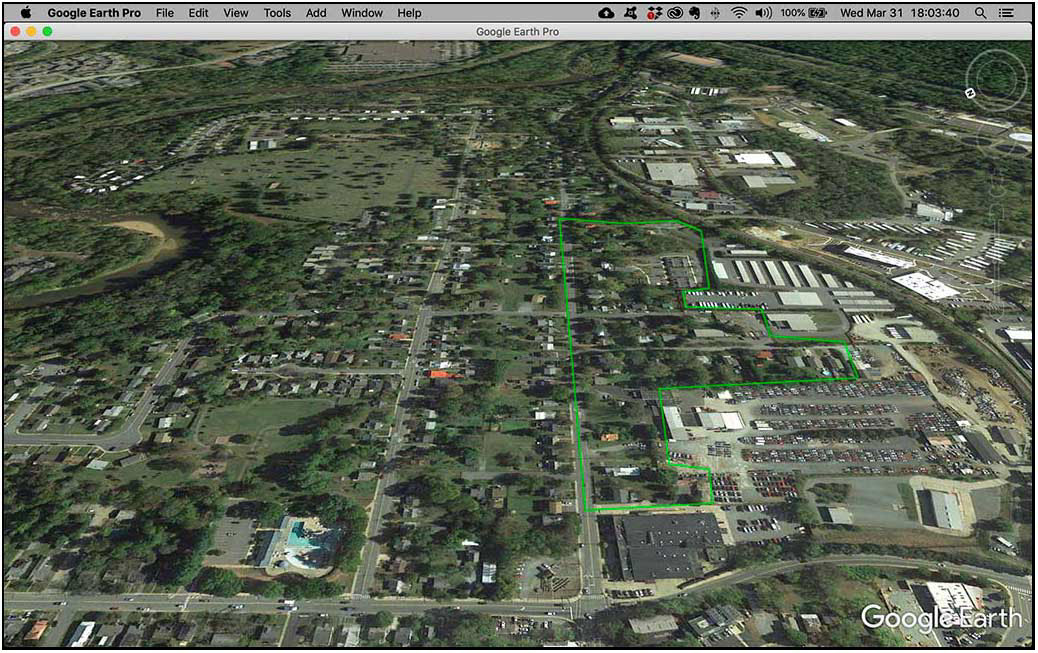

The crow’s eye view.

1300 Chesapeake

The houses’ average age is 75 years old, half of them were built by the end of World War II, the other half were finished at the end of the Korean War.

1302 Chesapeake Street

The homes were built by blue-collar people.

1304 Chesapeake

To this day, not one of them features a garage or a swimming pool.

1306 Chesapeake

Nine of the houses are rented, thirteen are owner occupied

1308 Chesapeake

The houses don’t tend to flip, the average last date of sale was twenty-two years ago.

1310 Chesapeake

Over the years I’ve made the acquaintance of a handful of the residents while walking by.

1314 Chesapeake

I’ve met a librarian, a plumber, a teacher, a postal worker, a United States Marine

1316 Chesapeake

a boat captain, students, an X-ray tech, a museum worker and an IT person.

1318 Chesapeake

These houses average 1100 square feet finished living area.

1320 Chesapeake

The average lot the houses sit on is 0.18 acres, that is five dwelling units per acre (DUA).

1322 Chesapeake

Their average assessment is 290 thousand dollars.

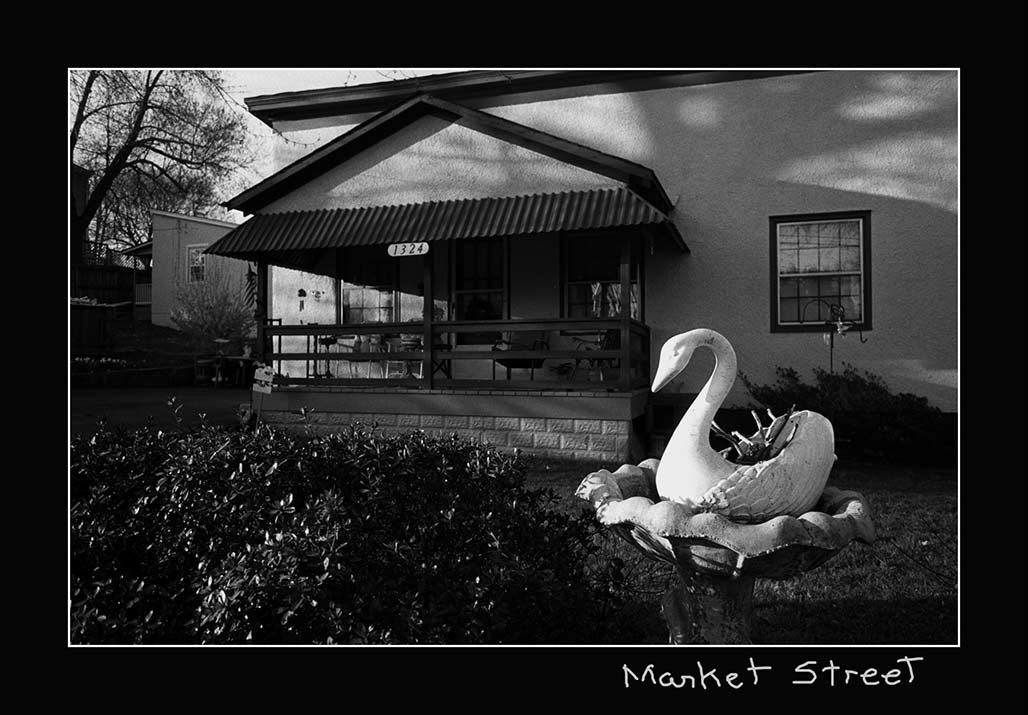

1324 Chesapeake

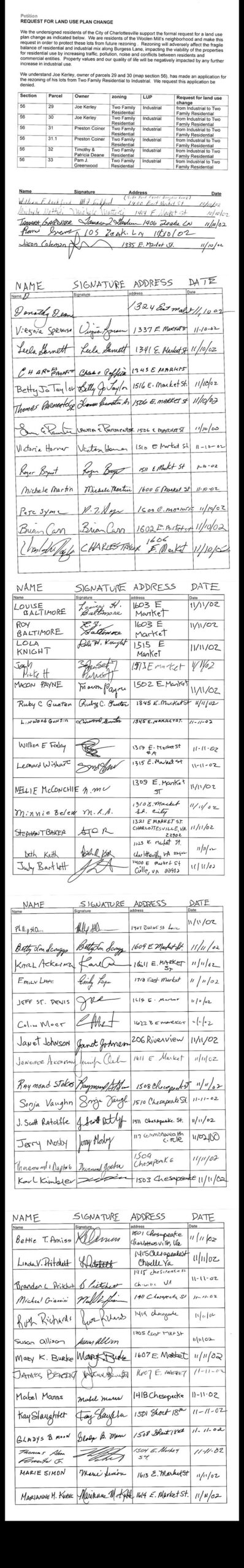

The 22 homes, are stable, they are occupied, they are the refuge of families who moved to the neighborhood and planned to stay.

1326 Chesapeake

I believe that painting this block with a medium intensity residential (MIR) land use designation is not acceptable planning.

1328 Chesapeake

The MIR designation is unfair to the residents

1330 Chesapeake

The designation will target their houses for demolition, it is an economic bulldozer.

.

1332 Chesapeake

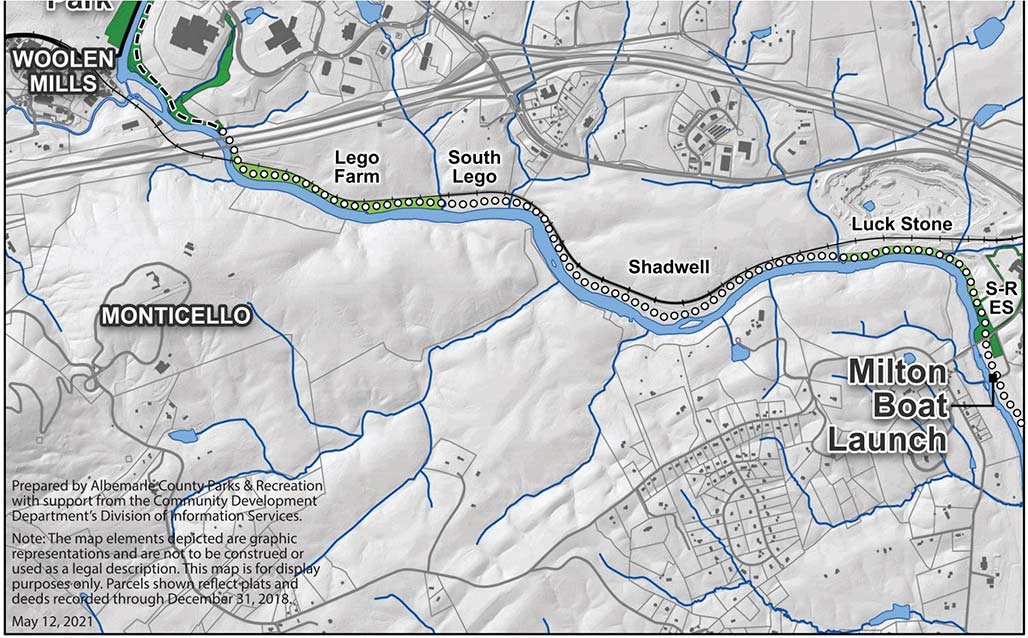

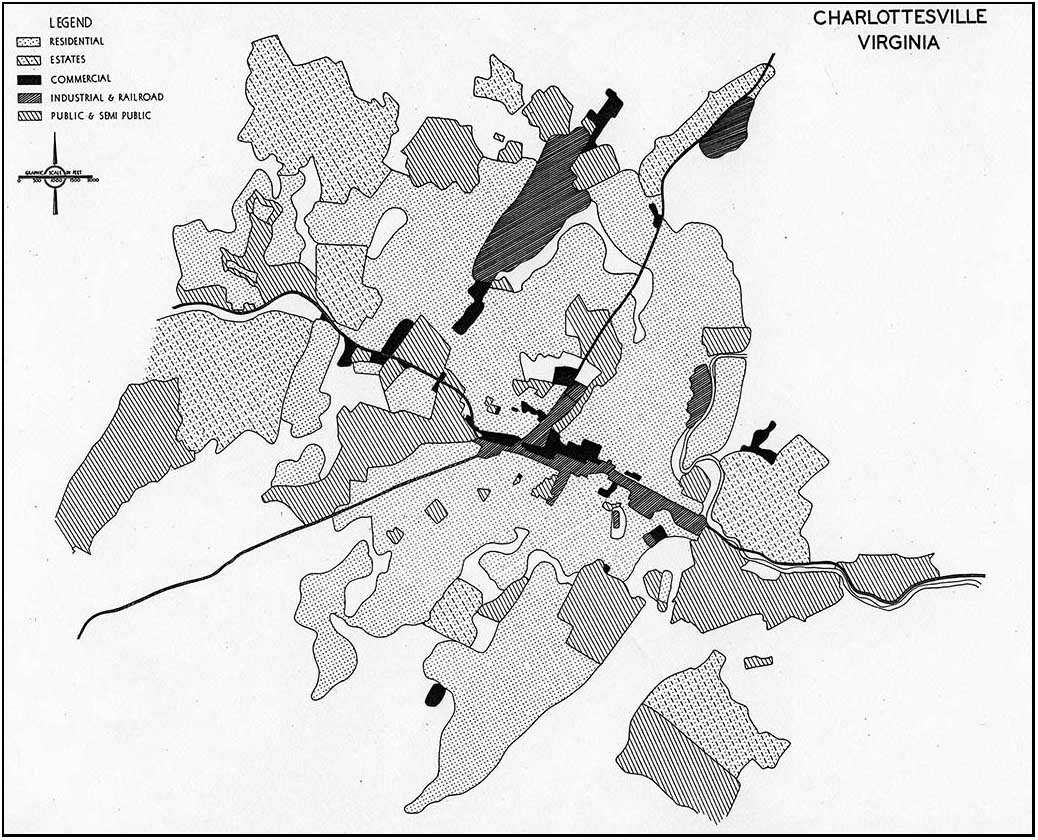

The Woolen Mills neighborhood requested a small area plan from the City in 1988.

1334 Chesapeake

If the City had provided a framework for public and private investment decisions to the Woolen Mills by means of a small area planning process decades ago the current action could make sense.

1336 Chesapeake

But there has been no small area plan.

1338 Chesapeake

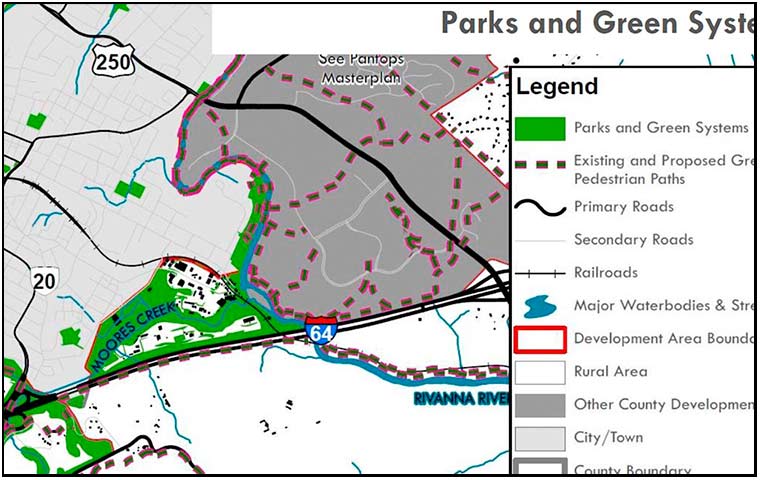

I encourage Council to get scientific, to use the tools of Archimedes and Galileo, math and maps.

Pick some baselines to trigger small area plans in neighborhoods with significant proposed up-zoning.

1340 Chesapeake

For example, if a rezoning will potentially displace 50% of the area’s existing residents, perform a Small Area Plan.

If a rezoning will increase DUA by more than 10X, perform a Small Area Plan.

1342 Chesapeake

Effective city planning is done by having comprehensive neighborhood plans that share the benefits and burdens required to keep the City humming along in an equitable, healthy fashion.

1344 Chesapeake

The 2021 Comprehensive Plan is intended to guide the coordinated harmonious development of the territory within the City to promote the health, safety, order, convenience, prosperity and general welfare of the city’s inhabitants.

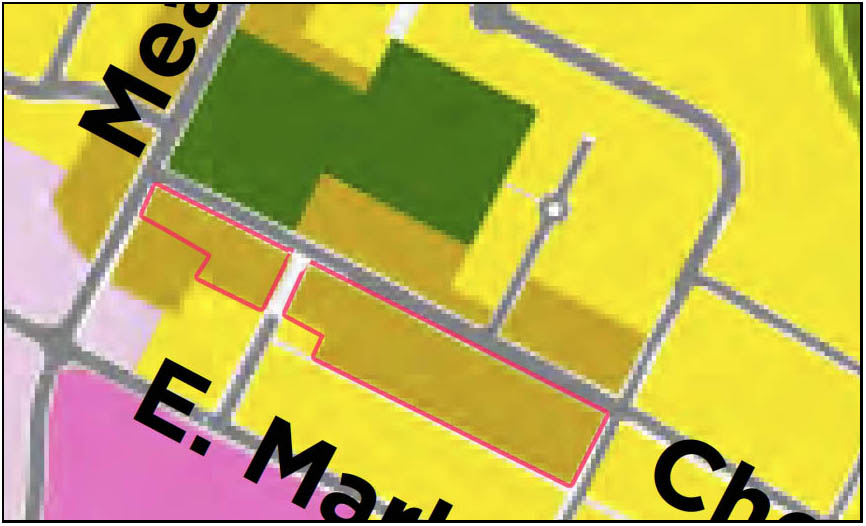

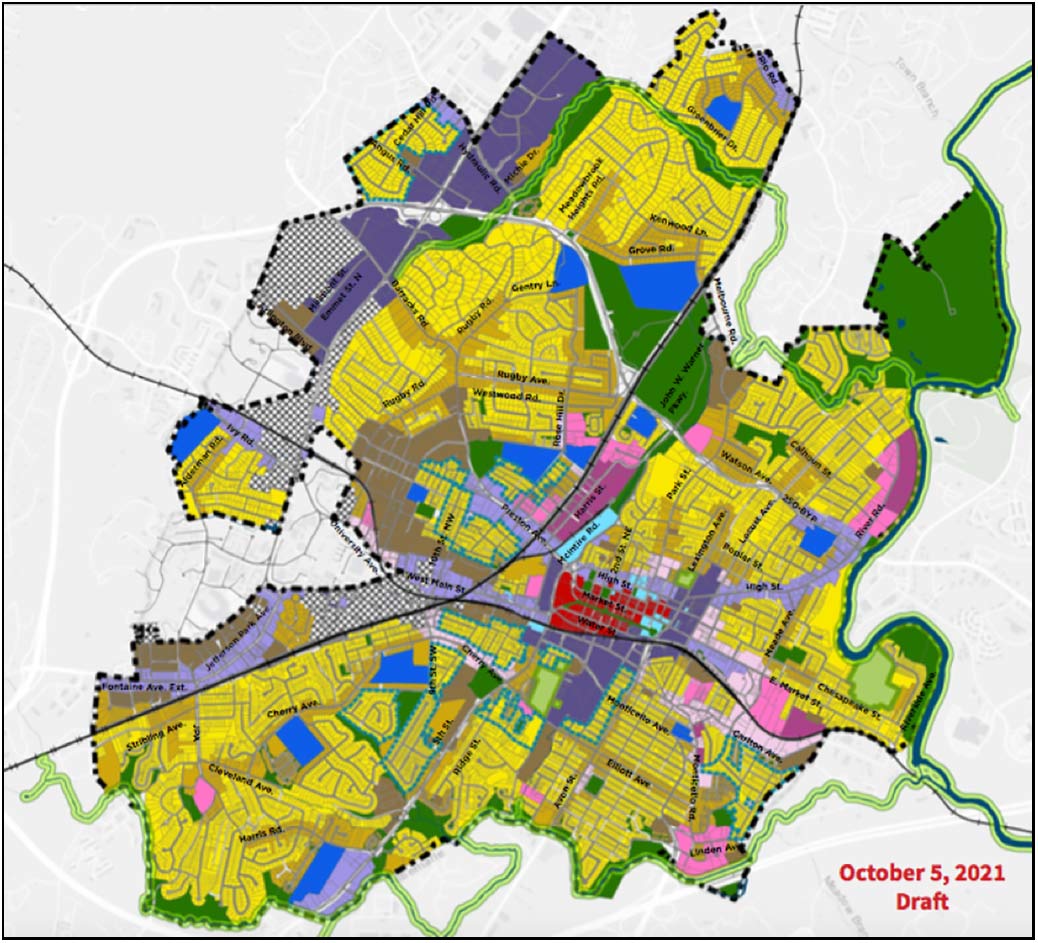

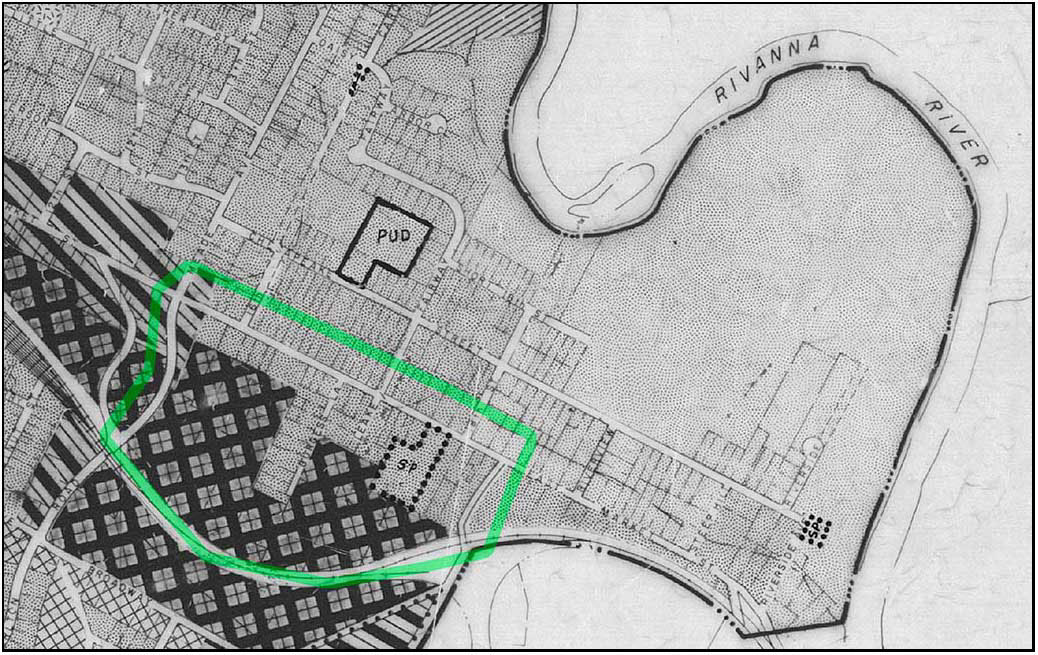

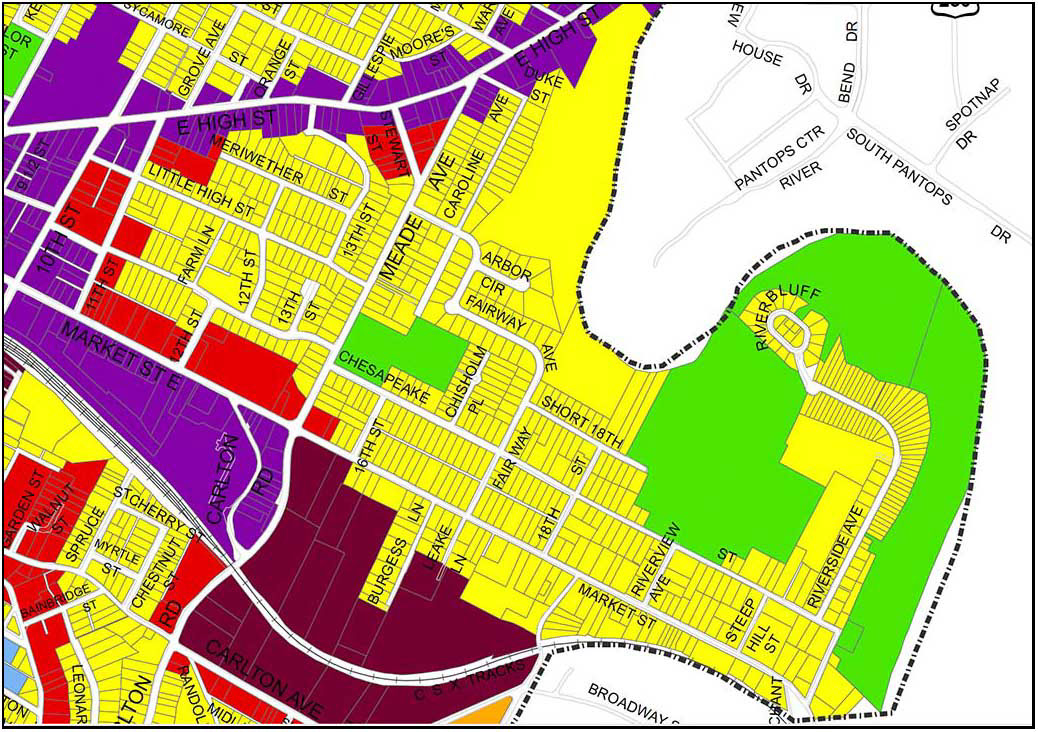

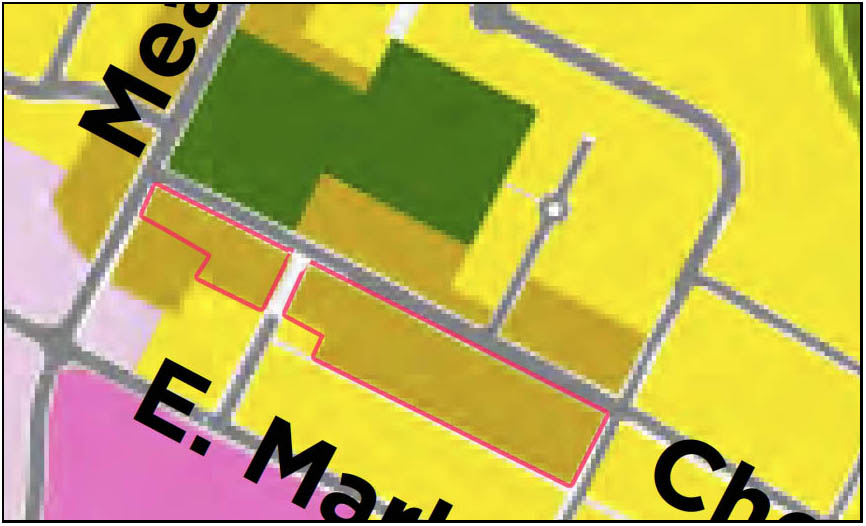

The 22 are in the beige, outlined in red.

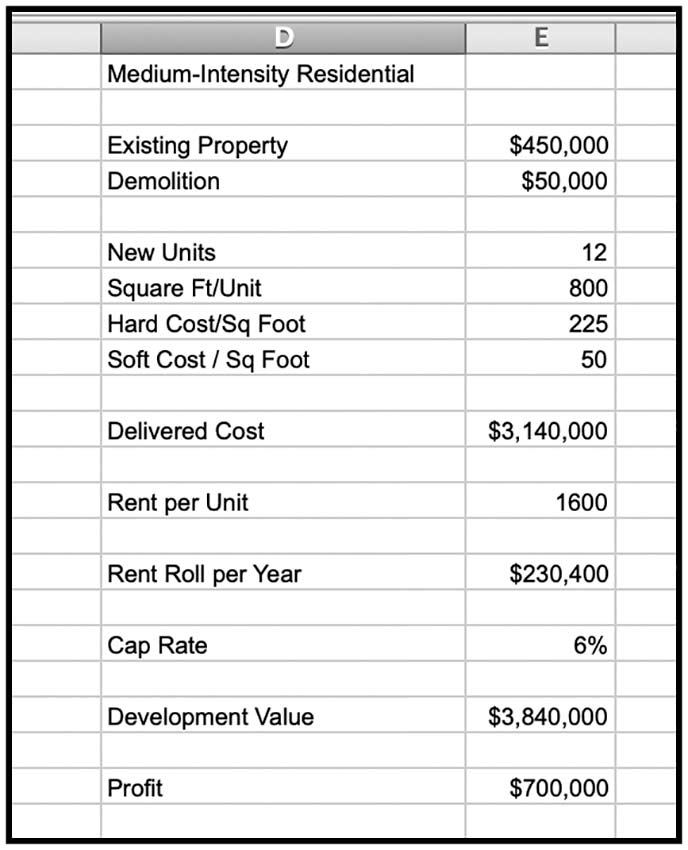

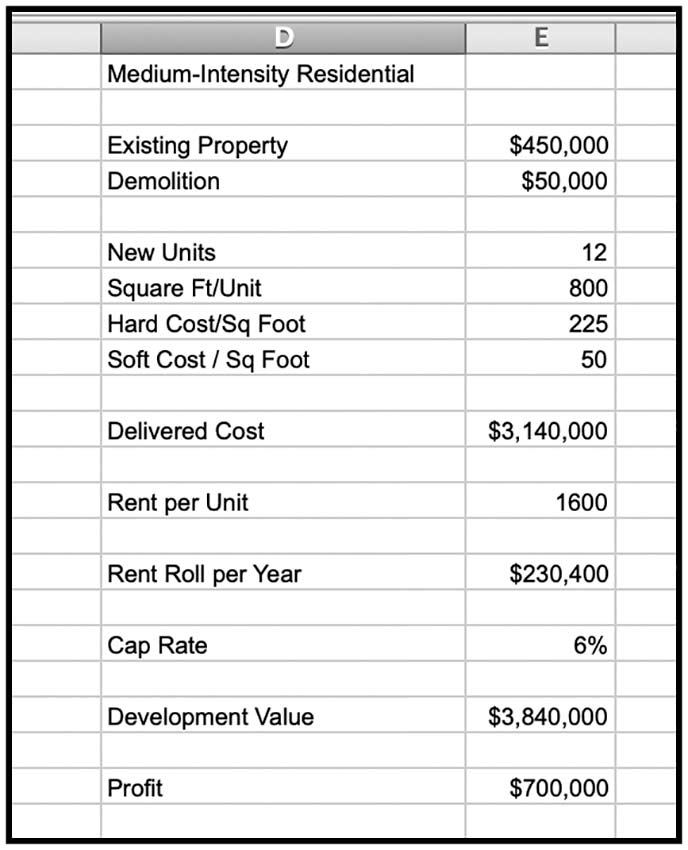

City Council will decide on the fate of these 22 houses in the next few weeks when they vote on the Future Land Use Map, a part of the not yet approved Comprehensive Plan. Currently, the map shows these humble houses being “redesignated” to a much more intense use known as “medium intensity residential”.

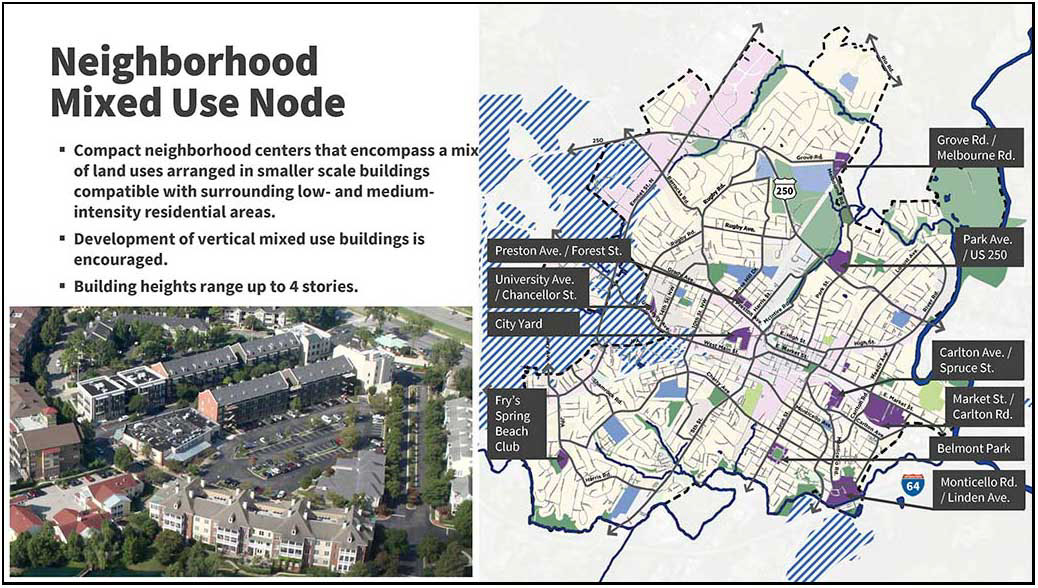

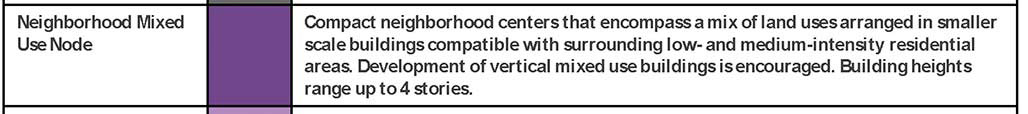

About the medium intensity residential (MIR) the urban planners say:

Medium Intensity Residential: Increase opportunities for housing development including affordable housing, along neighborhoods corridors, near community amenities, employment centers, and in neighborhoods that are traditionally less affordable.

In the case of the 22. These houses, on the spectrum of CHO housing, are affordable. To me, they don’t seem to fit the planners’ criteria. These houses are on a neighborhood street not a “corridor”. The houses aren’t near employment centers.

The MIR designation will potentially result in the demolition of these residences.

What could replace one of these houses once it was demolished? The planners say:

Form + Use:

Allow up to 12 residential units (depending on site characteristics and context, to be further defined in the zoning ordinance; many areas may be limited based on lot size and other factors)

Allow structures up to 4 stories (depending on site characteristics and context, to be further defined in the zoning ordinance; many areas may be limited based on lot size and other factors)

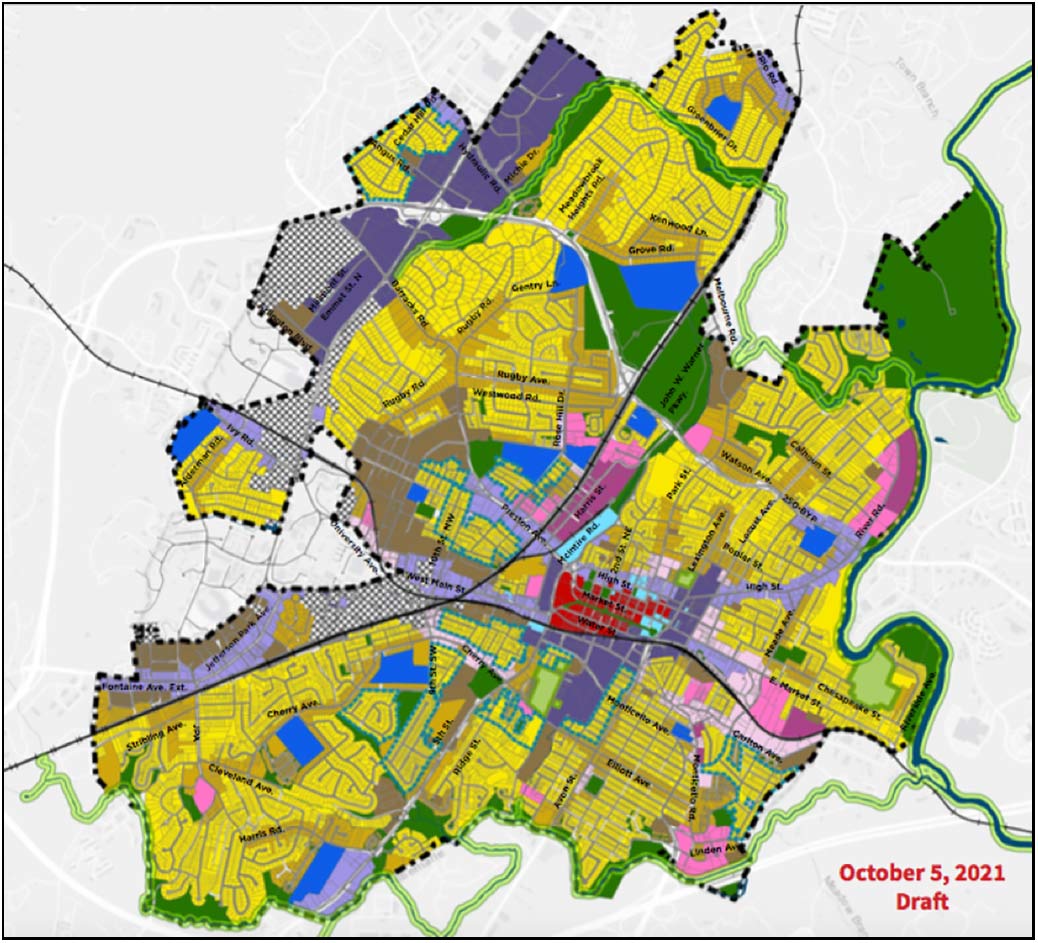

draft Land Use Plan

All the neighborhoods in beige are similarly threatened.

Bye-bye.

(I would encourage all concerned to write to City Councilors and to participate at the Council meeting on this subject November 15, 2021. Details of how to participate are available here) https://cvilleplanstogether.com/

Medium-Intensity Residential: Maximum-Intensity Pain

Medium-Intensity Residential needs to be scaled back in both scope and intensity. It is too much to ask people who bought in R-1 neighborhoods (over 60% of the parcels designated for Medium-Intensity Residential) to accept 12-unit (and possibly larger) buildings and 4+ stories, and it is not necessary for making our housing market more flexible, given other changes under the FLUM. The areas designated – changing up the last minute — do not make sense. MIR areas actually have a lower average Walkscore than General Residential. They lack critical infrastructure and some are so far below required density to support commercial amenities that their ultimate arrival is highly uncertain. There is no precedent for buildings above 3.5 stories in most of these areas. High-Intensity residential, on the other hand, shows clear differences — high walkability, transit access, existing infrastructure and height. With MIR, we could end up with a “worst-of-all-worlds” situation of having a scattering of MFH buildings isolated from amenities. And folks living in MIR feel targeted, because there is no compelling explanation of why their blocks should face a much more extreme transformation than nearly identical blocks nearby. If you need the MIR category to exist, scale it back to a few areas already adjacent to amenities, existing density and infrastructure.–CFRP

The Comprehensive Plan can go forward without a finalized land use map. Move head with the CP, move ahead with the many non-map aspects of the Affordable Housing Plan. But the map ought to be done in conjunction with plot-by-plot zoning. This is how planning usually works.–CFRP